Sector Facts and Figures

| Sector Facts and Figures | |

| OUTPUT | |

Sector GDP Share of Canadian GDP | $552.7 billion 28.0% |

| TRADE | |

| Exports | $10.2 billion |

| Imports | $12.0 billion |

| Foreign Trade Balance | -$1.8 billion |

| EMPLOYMENT | |

Total Employment 10-year change | 14,708,000 +17.2% |

| Percentage of part-time workers | 26.6% |

| Average hourly wage | $26.24/hr |

10-year real wage change | +2.1% |

| Average Work Hours/Week | 31.7 |

| ENVIRONMENT | |

Greenhouse Gas Emissions (2022) 10-year change Share of Canadian industry total | 132,750kt +0.7% 21.0% |

| LABOUR | |

| Union Coverage Rate | 33.0% |

| Unifor Members in the Industry | 8,000 |

| Share of Total Unifor Membership | 2.5%

|

| Number of Unifor Bargaining Units | 290 |

Unifor in the General Services Industry

Unifor's general services sector encompasses close to 95,000 members from various industries, including hospitality, healthcare, education and other industries that are outlined in specific Unifor sector profiles. The remaining 8,000 members covered here provide essential services that contribute substantially to Canada's social and economic well-being. Members in ‘other services’ work in diverse fields, including security, cleaning, administrative support, employment services, and municipal or government support.

While union coverage sits at 33% for the service sector as a whole, this figure is significantly skewed by public sector industries where coverage routinely exceeds 70%. Coverage tends to be substantially lower in the other services sector.

Bargaining unit sizes vary significantly, ranging from four to 425 members. Key employers include Securitas Canada, SerVantage, Sunshine Coast Regional District, and Mount Pleasant Group of Cemeteries. Over half of Unifor's members in this sector are located in Ontario.

| Select Unifor Employers | Approx. # Members |

| Securitas Canada | 425 |

| SerVantage | 306 |

| Sunshine Coast Regional District | 286 |

| Mount Pleasant Group of Cemeteries | 190 |

Current Conditions

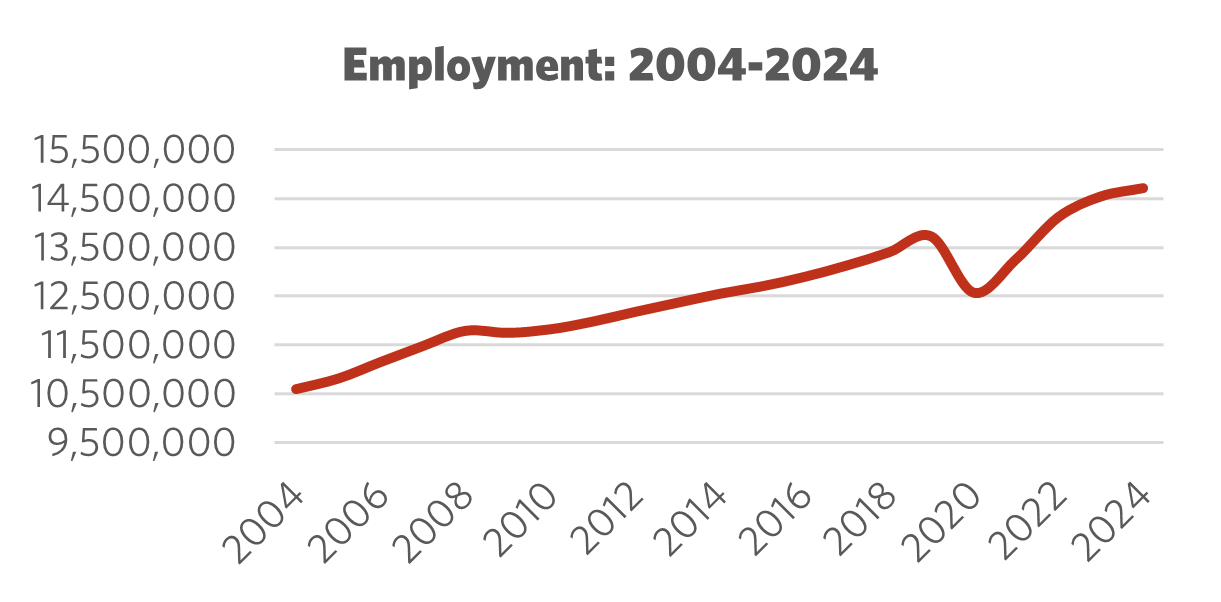

The service industry has experienced continuous growth, reflecting Canada's shift towards a service-based economy. For every job lost in the goods-producing sector, multiple jobs have been created in the service industry. In 2024, nearly 15 million Canadians were working in the service sector, representing a 17% increase over the past decade. Although notorious for low-wage and precarious work in key segments such as hospitality, retail and care work, the services sector is an economic powerhouse, accounting for 28% of the nation's gross domestic product.

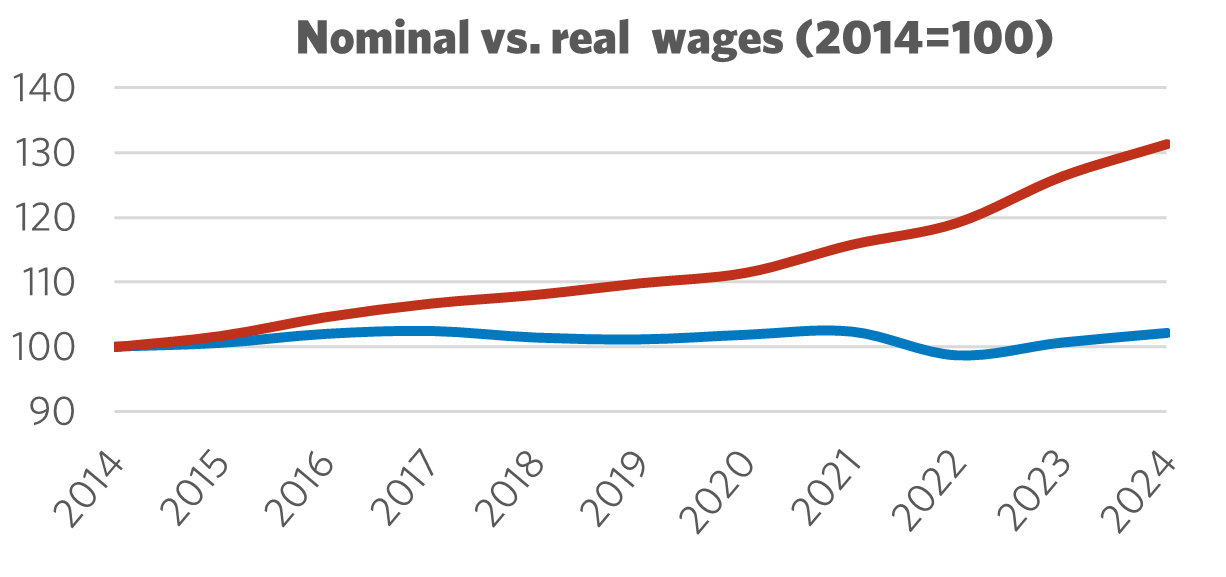

Service sector workers in Canada face significant economic pressures, primarily driven by persistent inflation, a widening cost-of-living crisis, and the indirect effects of trade and economic policies. These factors have eroded purchasing power and contribute to the financial instability of service workers. As prices for essential goods and services, such as food and housing, soared post-pandemic, wages failed to keep pace, significantly diminishing the purchasing power of workers in this industry.

The economic pressures on businesses, including higher input costs and relatively low profit margins, often lead to strategies aimed at cutting labour expenses, including efforts to thwart unionization, an over-reliance on part-time work and investments in labour displacing automation technology. This frequently translates into lower general wage increases for workers in affected industries. Simultaneously, a U.S. provoked trade war and persistent threats of tariffs on consumer goods, have driven up prices on certain items, contributing to inflationary pressures. This creates a challenging situation where workers are squeezed from both sides: their pay growth is slowed due to corporate cost-cutting, while the cost of living for everyday products increases.

The increase in service jobs, which are largely dominated by women workers, non-core aged workers and racialized workers, has led to a workforce with intersecting needs that differ fundamentally from traditional, male-dominated manufacturing sectors. According to 2023 data, approximately 57% of service sector workers are women, and 25% identify as a visible minority. This compares to approximately 28% women and 20% visible minorities in the manufacturing sector. Adapting organizing efforts and bargaining strategies as well as legislated employment standards to address the needs of female and racialized Canadians is crucial to serving the diverse workforce in the service sector. The fragmentation of employment locations has resulted in inconsistent bargaining outcomes. To improve the working conditions of workers in this industry, a coordinated sectoral approach to collective bargaining must be explored by lawmakers, one that pursues similar economic gains and advances unified proposals at each negotiating table. Prioritizing wages and job security provisions on a coordinated basis, as well as employer-provided health benefits and pensions, will help address precariousness and income insecurity – two prevalent issues in the sector.

Unifor must continue to advocate for card check certification from governments to expand unionization to traditionally hard-to-reach workers. In addition, pushing governments to enact labour protections, such as fair scheduling, the right to disconnect, and enhanced labour standards for temporary and gig economy workers, is crucial to improving overall conditions in the sector as well.

Figure 1: Employment 2004 – 2024

Figure 2: Nominal vs. Real Wages (2014 = 100)

Moving Forward: Developing the General Services Industry

An increasing number of service workers are required to meet growing demand in this sector. However, these jobs are often associated with higher precariousness and lower wages compared to jobs in goods-producing sectors, like manufacturing. The service sector is characterized by small workplaces, high employee turnover, and dispersed workforces, which complicate organizing efforts. The varied interests of workers also make it challenging to build solidarity and negotiate collective agreements. Technological advancements, such as automation and artificial intelligence, pose a threat to job security in this sector.

The fragmentation of employment locations has resulted in inconsistent bargaining outcomes. To improve the working conditions of workers in this industry, a coordinated sectoral approach to collective bargaining must be explored by lawmakers, one that pursues similar economic gains and advances unified proposals at each negotiating table. Prioritizing wages and job security provisions on a coordinated basis, as well as employer-provided health benefits and pensions, will help address precariousness and income insecurity – two prevalent issues in the sector.

Unifor must continue to advocate for card check certification from governments to expand unionization to traditionally hard-to-reach workers. In addition, pushing governments to enact labour protections, such as fair scheduling, the right to disconnect, and enhanced labour standards for temporary and gig economy workers, is crucial to improving overall conditions in the sector as well.

Sector Development Recommendations

- Implement a coordinated sectoral approach to collective bargaining that aims for consistent economic gains and unified proposals across various negotiating tables to improve working conditions and address income insecurity.

- Support and advocate for card check certification to facilitate unionization efforts, particularly for traditionally hard-to-reach workers in the service sector, thereby enhancing their representation and rights.

- Push for stronger labour protections, including fair scheduling, the right to disconnect, and improved standards for temporary and gig economy workers, to ensure better working conditions and security for a diverse workforce.

- Develop and implement organizing and bargaining strategies specifically designed to address the unique needs of female and racialized workers in the service sector, fostering solidarity and enhancing collective negotiating power.