Sector Facts and Figures

| Sector Facts and Figures | |

| OUTPUT | |

| Total GDP | $2.27 trillion |

| TRADE | |

| Exports | $780.8 billion |

| Imports | $765.7 billion |

| Foreign Trade Balance | +$15.1 billion |

| EMPLOYMENT | |

Total Employment 10-year change | 18,191,631 +16.4% |

| Percentage of part-time workers | 18.1% |

| Average hourly wage | $35.20/hr |

10-year real wage change | +8.8% |

| Average Work Hours/Week | 35.6 |

| ENVIRONMENT | |

Industry GHG Emissions (2022) 10-year change | 631,808 kt -4.8% |

| LABOUR | |

| Union Coverage Rate | 30.2% |

| Unifor Members in the Economy | 320,000 |

| Number of Unifor Bargaining Units | 2,882 |

Unifor in the Canadian Economy

Unifor is the largest labour union in the private sector and its 320,000 members span 2,882 bargaining units, 617 locals, and 25 unique industries, spread out across every region of Canada. Around one out of every six unionized workers in the Canadian private sector is a Unifor member.

Approximately 33,000 Unifor members work in the communications sector and 49,000 work in transportation industries, including air, rail, road and marine transport. More than one in four Unifor members work in manufacturing, led by auto assembly with 36,000 members, while over one in six members work in the resources sector, which includes energy, forestry and mining. Close to 95,000 members work in the services sector, accounting for around 30% of Unifor’s total membership. Just under half of all Unifor bargaining units are located in Ontario, followed by Quebec (24%), Atlantic Canada (11%) the Prairies (9%) and British Columbia (8%).

Current Conditions

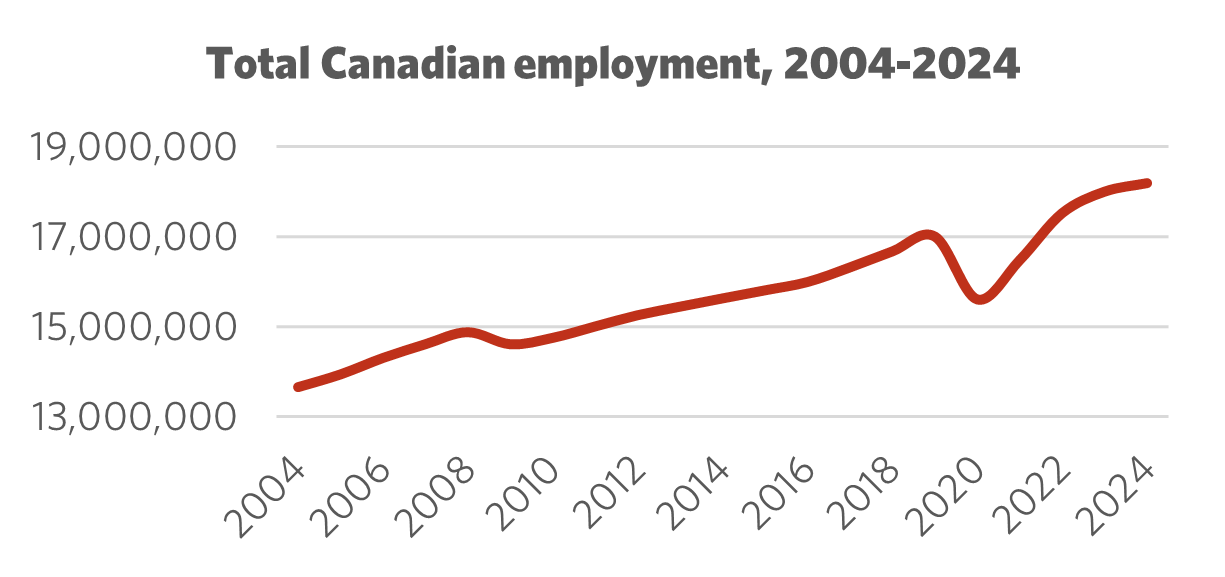

Canada bounced back from the COVID-19 pandemic with remarkable job and economic recovery. After a contraction of nearly 5% in 2020, gross domestic product (GDP) surged by 6% in 2021 and 4.1% the following year. Meanwhile, employment levels – which had fallen by a disastrous 8.2% in 2020, putting more than 1.4 million Canadians out of work – rebounded by 5.6% in 2021 (+877,400) and 6.3% in 2022 (+1,044,500), adding close to 2 million jobs back to the economy.

Supply constraints during the pandemic were well publicized, with public health measures and the physical toll of the COVID-19 virus wreaking havoc on extended and vulnerable global supply chains. Broken supply lines contributed to abnormally high inflation from 2021 to 2023, with average prices in Canada jumping by 3.4% in 2021, 6.8% in 2022 and 3.9% in 2023 – well above the inflation-control range set by the Bank of Canada – causing an affordability crisis for most working people.

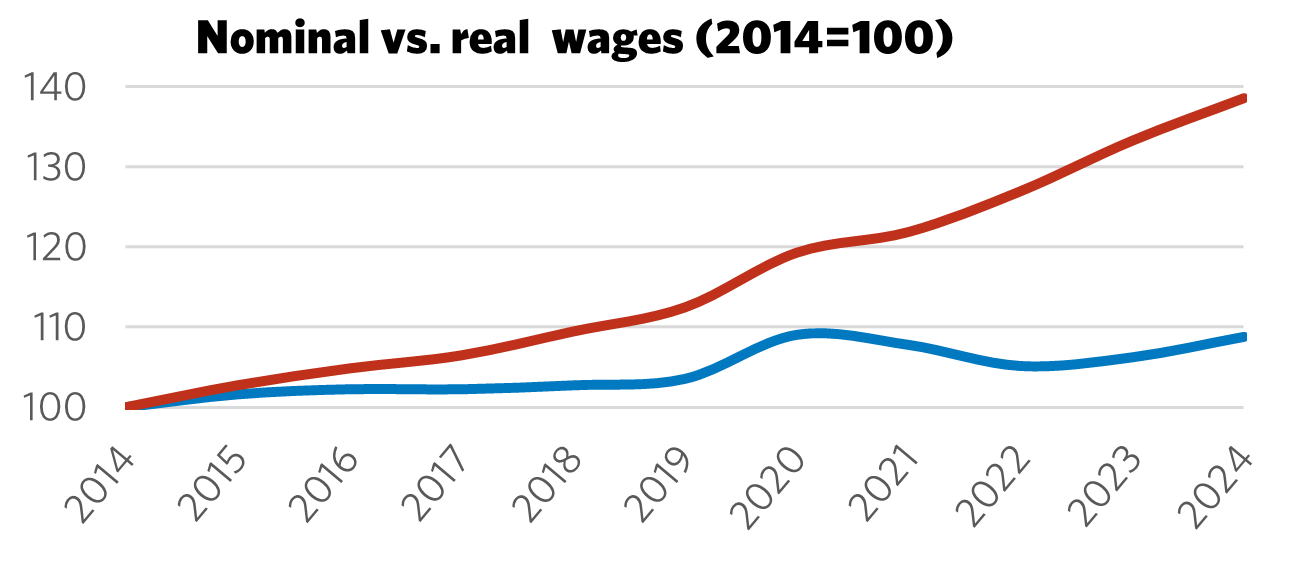

Initially, many central banks identified these inflationary pressures as transitory and linked to pandemic-related supply shocks, while a less-cited cause was the trend of companies using the cover of inflation to raise prices and earn excess profits. However, increasing political pressure to respond to higher prices led central banks to revert back to a decades-old playbook of linking inflation to low unemployment, wage growth and the release of pent-up demand, with central banks everywhere ratcheting up interest rates starting in 2022. Yet, a delayed increase in average hourly wages clearly indicates that wage growth was a response to, rather than cause of, higher prices as workers tried to keep up with the higher cost of living. And despite higher nominal wage growth in recent years, real wages were effectively flat between 2020 and 2024.

The predictable outcome of an accelerated bout of monetary policy tightening was to rapidly dampen economic activity and jobs growth across the country. Canada’s GDP growth fell to 1.6% in 2023 and 1.7% in 2024, while overall employment growth fell to 2.7% (+480,000) and 1.0% (+188,000) over the same period, respectively.

To make matters worse, Canada’s economy is now contending with an aggressive U.S.-provoked trade war, which threatens to devastate a highly interconnected and U.S. export-dependent industrial base. The Trump Administration’s tariff policies have had a disproportionate impact on Canada, bringing capital investment to a standstill. The national unemployment rate, which hit a historic low of 4.8% in July 2022, has since risen steadily higher, reaching 7% in May 2025 as tariffs impact key sectors. Youth unemployment, underemployment rates and the proportion of long-term unemployed (those searching for work for 6 months or longer) have all reached decades-long highs outside of the 2020-21 pandemic years. In short, the Canadian economy has entered a sustained period of labour market deterioration, uncertainty and economic decline.

Figure 1: Employment 2004 – 2024

Figure 2: Nominal vs. Real Wages (2014 = 100)

Moving Forward: Developing the Canadian Economy

The Canadian economy finds itself at a critical inflection point, with the post-pandemic recovery having long faded into the background while U.S. tariffs threaten key industries. The unemployment rate climbed substantially during the first few months of 2025 and average wage growth has moderated significantly, while several indicators suggest that the employment and wages slowdown will continue to worsen. Economic growth beat expectations in the first quarter of 2025, but household savings declined alongside corporate incomes. Notably, the manufacturing sector has lost around 55,000 jobs since the start of 2025, with the majority of these losses occurring since the Trump administration began to threaten and impose tariffs on Canada in February.

On the monetary front, inflation has fallen significantly, reaching the Bank of Canada’s target range at the start of 2024 and falling even further since then, down to 1.7% as of April 2025. However, subsequent interest rate cuts have had little effect on boosting Canada’s economy as a general climate of economic unpredictability – made worse by mounting U.S.-provoked trade tensions – has led companies to hold off on major capital investments and job-generating projects. The Bank of Canada has held off on further cuts, hoping to save some of its firepower to combat the impacts of tariffs on Canada’s economy. Meanwhile, Canadian workers continue to cope with higher post-pandemic prices at a time of spiking unemployment and growing precarious work. Fast-developing, and transformational technologies like artificial intelligence (AI), which still lack proper regulatory controls and guardrails, also pose threats to jobs and worker well-being.

Canada’s newly-elected federal government announced its intention to engage in ‘nation-building’ projects in coordination with provincial and territorial governments, both to combat the threat of tariffs and to build a more independent Canadian economy. There is a real danger, however, that governments and industries will simply override labour, Indigenous and environmental protections in their zeal to boost economic activity and overcome trade barriers. Governments must not trample on fundamental rights in the effort to deliver urgent, forward-looking economic growth. Instead, nation-building projects must be linked to the promotion of union density, wage growth and skilled trades apprenticeships, to ensure that such projects benefit Canadian workers.

Unifor has long called on governments at all levels to develop targeted, coherent industrial strategy through social dialogue with unions and industry representatives. For the Canadian economy to navigate the immense challenges it confronts, industrial policies will be vital to build a whole-of-supply-chain approach to reinforce Canada’s industrial capacity and build a truly independent economy. Unions and their allies across Canada must make it clear that deregulation is not a substitute for industrial policies.

Economic Development Recommendations

- Negotiate a permanent end to U.S. tariffs.

- As inflation subsides in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on supply chains, monetary policy must be geared towards revitalizing job growth and economic activity. Policymakers must systematically examine the contributions of corporate profiteering to recent increases in the cost of living and implement countermeasures accordingly.

- The federal government must ensure that "nation-building" projects launched to strengthen domestic industries and reduce dependency on external markets do not trample on fundamental labour, Indigenous and environmental protections.

- To ensure that Canadian workers benefit, nation-building projects should be linked to the promotion of greater union density, wage growth and skilled trades apprenticeships.

- Governments at all levels should work together to build coherent industrial strategies based on social dialogue with unions and industry to navigate Canada’s economic challenges effectively.