Share

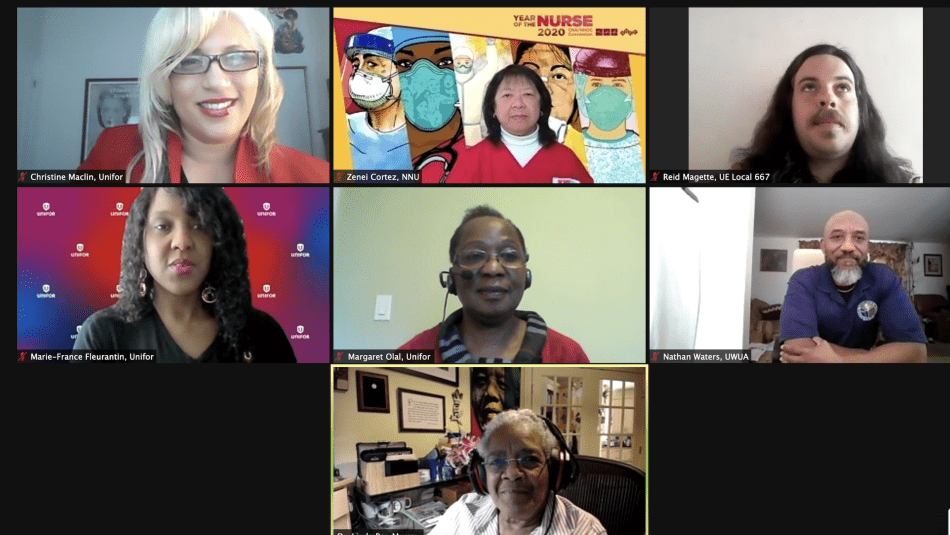

Coming together just days after a racist attack in Atlanta, Ga., participants in a recent webinar on racial justice reflected on both the history of racism in Canada and the U.S., and the work that must be done going forward.

“We saw a violent act of racism just this past week,” Unifor Human Rights Director Christine Maclin said as she opened the session by reading the names of six Asian women killed in Atlanta, along with two men.

“They were attacked because they were women and because they were Asian.”

The Together for Racial Justice webinar was held March 20 as part of the North American Solidarity Project, which Unifor is participating in along with several other unions across North America.

Participants shared stories of racism they have experienced, both on the job and as children.

Margaret Olal, a hotel worker in British Columbia who helped organize her workplace, told the story of a family staying at her hotel telling her to “go back to where she came from” and calling her a racial slur.

Both her co-workers and her manager told her to ignore it an go on with her work. Most of her co-workers were workers of colour who had often confronted racism on the job.

“They did not talk about it. Why? Because they were scared and it was the only job they had,” Olal said. “I carried this with me for many years until we became unionized.”

She was not alone.

Nathan Walters of the Utility Workers Union of America, told the story of protesters, including members of the Ku Klux Klan, pelting his school bus with rocks during integration in Pontiac, Mich.

“We had white teachers who were afraid of us, and we had black teachers who were trying to protect us.”

Marie-France Fleurantin of Unifor Quebec told the story of a neighbour when she was growing up in a Montreal suburb telling her she couldn’t come into the house because she is black.

“I couldn’t understand a thing. I couldn’t understand what was happening.”

Zenei Cortex, equity ambassador National Nurse United in the U.S., said racism becomes institutionalized in workplaces, including in healthcare, where it affects both workers of colour and their racialized patients.

“In my 41 years as a nurse, I have seen how racism sickens and kills our patients.”

Cortex said people of colour make up only 24.1% of the healthcare workforce in the U.S. but 54.1% of the deaths attributed to COVID-19. Workers of colour are often given inadequate PPE, or told to reuse PPE more often than their white coworkers, she said.

Participants also shared the work their unions are doing in their workplaces and communities to confront racism and build solidarity, through education, training and collective bargaining.

Asked by Maclin what it meant to be a good ally, Reid Magette from the American union UE said it meant listening, not trying to speak for workers of colour and using your privilege to help.

“Be out there and be at those protests – and let the white power structure that exists know that you will not be complicit in their games,” said Magette.

The panel concluded with an address from social justice advocate Dr. Linda Murray, who told the story of her granddaughter, who is committed to fighting racial injustice despite her father’s worries for her safety.

“She understands racism. She is tired of it. She’s going to do something about it. She’s 18,” Murray said.

The attacks in Atlanta show that white supremacy is alive and well, Murray said.

“Fury, not pride, is in my heart. As we look at last week’s events in Atlanta, we have to be clear what is going on here,” she said.

“It was an act of racism.”