Share

This past year, workers experienced unemployment on a scale never before seen in Canada. At its first wave peak in June 2020, some 2.7 million workers in this country had no job. The magnitude of these losses effectively paralyzed the Employment Insurance system, requiring alternative means of income support via the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). Since then, Carla Qualtrough, the Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Disability Inclusion, announced a temporary overhaul of EI qualifying rules, benefit payouts, and other measures to support eligible workers when CERB claims expire.

Unifor applauded the changes that took effect in September. Under new rules, there are no waiting periods, fewer qualifying work-hours and a new minimum benefit floor, among other changes including a new recovery benefit for those ineligible for EI. Unifor documented these and other changes in its fact sheet ‘What happens after the CERB?’ available online.

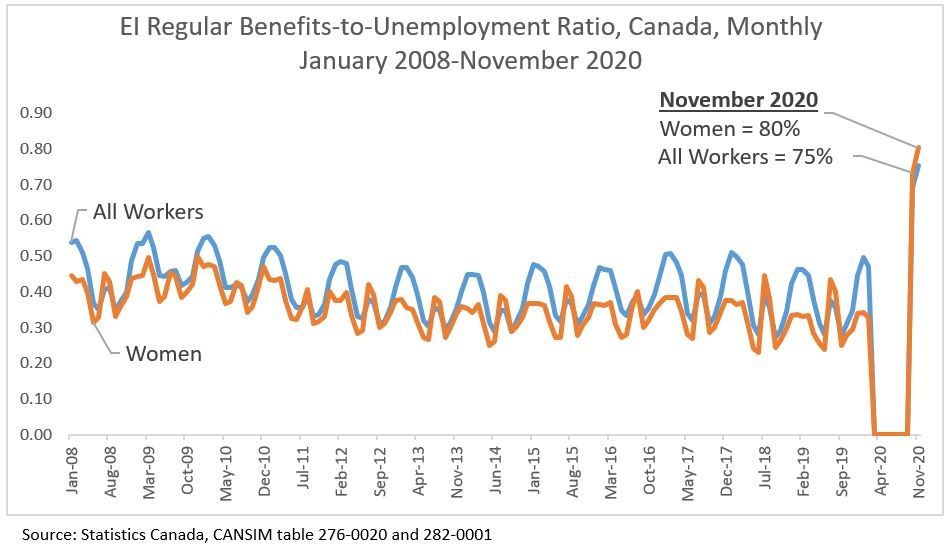

As expected, these temporary changes boosted EI accessibility in Canada. Two month’s worth of data now prove the point. In fact, last November, the share of unemployed workers receiving EI regular benefits (referred to as the ‘Benefits-to-Unemployment’ ratio, or B/U ratio) was 75 % (see table). That means, Employment Insurance benefits covered a full three-quarters of unemployed workers in Canada – a remarkable statistic, considering monthly coverage was just 40 %, on average, in pre-COVID times (for a great background on various EI measures, read Ricardo Tranjan’s work for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives).

There is an important equity dimension to these temporary EI changes too.

Women, for instance, benefited the most. According to the data, 80 % of unemployed women accessed regular benefits in November, more than doubling the average monthly access rate (36%) since 2008.

The significant loosening of entrance requirements (i.e. providing benefits to workers after attaining 120 insurable work hours instead of what is normally as high as 700) makes EI more accessible to those in precarious jobs struggling with erratic and undefined work schedules – jobs that overrepresent women and workers of colour.

By increasing the numbers of qualifying workers, the EI system is now doing what it’s supposed to – providing income security, and financial stability, to as many unemployed workers as possible.

When the Prime Minister issued a round of supplementary mandate letters to Ministers in January, he directed Minister Qualtrough to craft an EI modernization plan to improve access, including for those in precarious jobs. These emergency measures are a litmus test for broader reform.

It is unimaginable to think how the existing EI system could have carried workers through this pandemic, not when it effectively disqualifies more than half of unemployed workers (and nearly three-quarters of low-wage workers) from receiving even a nickel in income support.

The CERB was not only a lifeline to crisis-stricken workers it was also a wake-up call to EI system architects. Decades of destabilizing reforms to EI took Canada down the wrong path. As the data show, temporary measures offer a path toward permanent course-correction on policy.

With the pandemic still raging, there’s no better time to fix EI, once and for all.