Share

By Sune Sandbeck, National Representative, Research Department

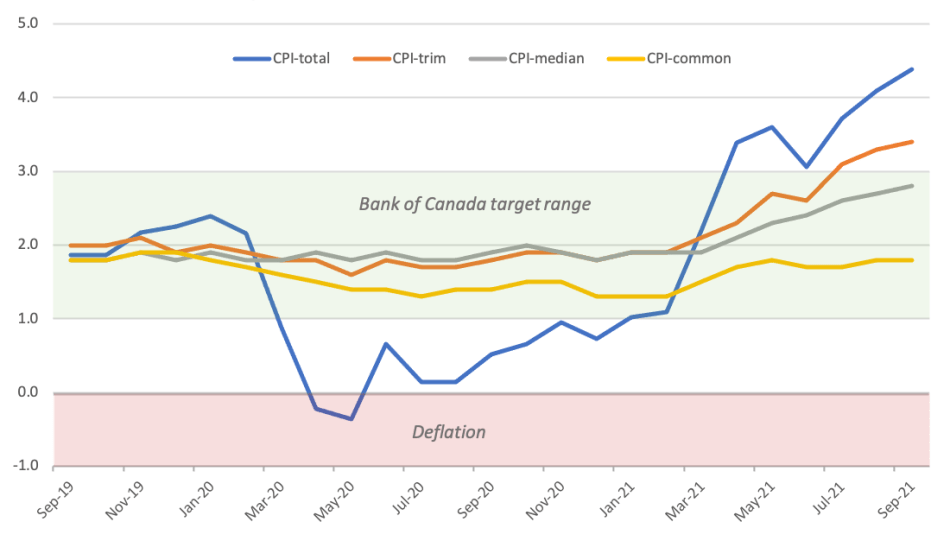

The debate over what to do about inflation has been heating up over the past few months. With the annual growth in the consumer price index (CPI) reaching 4.4% in September, calls are growing louder for the Bank to accelerate its plans to increase interest rates.

For many Canadians, the Bank’s apparent reluctance to react to the recent spike in inflation might be perplexing. After all, one of the main goals of any central bank is to ensure that inflation stays within a certain range – in Canada’s case, 1% to 3%.

However, what many media outlets and commentators have failed to explain is that the Bank’s main target is not CPI as a whole, but instead, what it calls ‘core inflation.’ Since CPI measures the overall price level, changes in CPI may reflect price movements caused by temporary supply shocks or factors affecting specific sectors rather than core inflation linked to underlying changes in the economy.

Simply put, the Bank cannot afford to overreact to price changes that are temporary or that only affect some goods and not others. Raising rates too quickly while the country is still recovering from an unprecedented economic crisis might dampen economic activity and risk another recession.

The Bank therefore has the difficult task of trying to separate out core inflation from the background noise of temporary price movements. How does it do this? Since 2016, the Bank’s preferred measures of core inflation are CPI-trim, CPI-median and CPI-common.

For a given month, both CPI-trim and CPI-median remove price changes in the upper and lower portions of the price change distribution (the highest and lowest 20% for CPI-trim; the entire distribution apart from the price change at the 50th percentile for CPI-median). While this reduces volatility, it can’t tell us whether temporary price movements are still affecting the measurement.

CPI-common, however, uses a statistical model to determine how much of the change in CPI is caused by price movements common to all baskets of goods/services while eliminating price movements linked to specific goods/services that are more likely to be temporary.

As Figure 1 illustrates, total CPI, CPI-trim, and CPI-median have been trending towards or above the upper 3% limit of the Bank’s target range, but CPI-common has been comparatively stable and has remained below 2%. This shouldn’t be surprising in light of the widely reported disruptions in global supply chains and the increased cost of fuel in recent months. The Bank’s policymakers are therefore likely concluding that recent price increases have been transitory rather than caused by a sustained uptick in core inflation.

Figure 1: Measures of CPI and Core Inflation (%)

However, while the Bank’s reluctance to tighten monetary policy until the data warrants it is in the best interests of Canada’s continued economic recovery, it’s cold comfort to Canadian workers for whom inflation is very real. Record low interest rates have also contributed to an explosion in housing prices, increasing debt burdens and the appearance of asset bubbles in everything from stocks to digital collectibles (so-called NFTs).

What this seemingly contradictory set of facts reveals is that we cannot rely on central banks to serve as silver bullets during times of economic uncertainty. Government has a fundamental role to play in building affordable housing, limiting financial speculation and increasing union density so that workers can bargain fairer wages for themselves.