Background

Our union has developed two prior bargaining programs, the first in 2016 and the second in 2019 (followed by a special pandemic recovery-based bargaining program in 2021). The bargaining program outlines broad Unifor priorities and presents new, ambitious ideas for bargaining committees to consider in their negotiations.

This year’s consultations will culminate in a national bargaining summit held in conjunction with our Canadian Council meetings in August.

In the weeks’ ahead, you will receive additional information on the schedule from Unifor’s Regional Directors. I urge everyone to identify the strategy session located in their home community, or those located nearby, and plan to attend and actively participate. This information will include details on how to register for the sessions as well.

Bargaining Workers’ Power Report

Unifor’s Collective Bargaining Program Report (PDF)

Contents

Bargaining Workers' Power: Project Timeline

Economic and Labour Market Climate for Workers

- Employment

- Wages

- Inflation

- Inclusivity/Human Rights

- Climate change/industrial transition

- Conclusion

Priority Issues and Union Positions

- Wages and Income Security

- Health and Safety

- Benefits

- Pensions and Retirement Security

- Human Rights, Inclusion, and Workplace Equity

- New Technology, Climate Change, and the Future of Work

- Workforce Attraction and Retention

- Job Security and Precarious Work

- Union Building

- Conclusion

Summary of Unifor’s Collective Bargaining Program Positions

- Phase One: Preparing for Bargaining

- Phase Two: The Bargaining Process

- Phase Three: Ratification

Letter from the National Officers

Collective bargaining is an essential tool when building workers’ power. When workers flex their muscle at the bargaining table, everyone benefits. When workers come together to identify common concerns, present creative solutions, and fight to make gains, we can effectively challenge corporate power, change lives, and take back control over an otherwise precarious and unfair economy.

Unifor is a union of 315,000 members covered by approximately 3,000 collective agreements across Canada. At any given time, thousands of members are engaged in collective bargaining. It is the core activity of our union, and no two sets of bargaining are the same. We recognize that maximizing our effectiveness at the bargaining table requires significant resources, attention, and strategic thinking between local unions and across industries. This is the spirit behind our Bargaining Workers’ Power project that led to the production of this new National Collective Bargaining Program.

Our Program presents a series of ambitious, cross-sector proposals and commitments for Bargaining Committees and staff to table when entering contract talks. In certain cases, the contents of the Program serve as directives – expectations of items that must be negotiated. In other cases, the Program presents creative ideas on how collective bargaining agreements can become more responsive to a changing economy, and the needs of workers.

This Program is a result of over five months of cross-country dialogue with more than 1,700 local union and bargaining committee representatives. From February to June 2023, we held 45 regional strategy sessions in communities across Canada. We listened to members talk about the challenges they face at work, as well as their top priorities in bargaining. We heard how difficult the past few years have been for workers, during the pandemic, and how the post-COVID economy has in many cases changed little from the one before it. These were honest and necessary discussions.

At the same time, members shared with us their vision for a better economy. Most importantly, they provided inspired ideas on how we can achieve a better world – through collective bargaining and solidarity.

We are very proud to present to you this final report. We are grateful to the members, local union leadership and staff who not only made this possible, but used this opportunity to build a stronger, more engaged union.

In solidarity,

Lana Payne, National President

Len Poirier, National Secretary-Treasurer

Daniel Cloutier, Québec Director

Acknowledgments

The National Collective Bargaining Program was made possible by the hard work and dedication of the Bargaining Workers’ Power Working Group, national staff as well as countless members and local union leadership.

Co-Chairs

Olivier Carrière, Executive Assistant to the Quebec Director

Shane Wark, Assistant to the National Officers

National President’s Office

Roxanne Dubois, Executive Assistant to the National President

Regional Directors

Gavin McGarrigle, Western Region Director

Jennifer Murray, Atlantic Region Director

Naureen Rizvi, Ontario Region Director

Regional Council Chairs

Shinade Allder, Ontario Council

Sophie Albert, Quebec Council

Matt Blois, Atlantic Council

Guy Desforges, Prairie Council

Leanne Marsh, British Columbia Council

National Executive Board

Dereck Berry, Black, Indigenous, Workers of Colour

John D’Agnolo, Auto Sector

Dana Dunphy, Hospitality and Gaming Sector

Chris Garrod, Rail Sector

Yves Guérette, Forestry Sector

Julie Kotsis, Media Sector

Tammy Moore, Aviation Sector

Staff (including Working Group participants and segment authors)

John Breslin, Director, Skilled Trades

Josh Coles, Director, Member Mobilization and Political Action

Graham Cox, Research Department

Anthony Dale, Senior Director, Legal and Constitutional Matters

Angelo DiCaro, Director, Research Department

Robin Fairchild, Director, Education Department

Erin Harrison, Research Department

Marc Hollin, Research Department

Sandeep Kakan, Director, Pensions and Benefits Department

Simon Lavigne, Research Department

Niki Lundquist, Senior Director, Equity and Education

Karen Marchesky, Research Department

Sarah McCue, Communications Department

Kathleen O’Keefe, Director, Communications Department

Tracey Ramsey, Director, Women’s Department

Sune Sandbeck, Research Department

Vinay Sharma, Director, Health, Safety & Environment Department

Kaylie Tiessen, Research Department

Bargaining Workers' Power: Project Timeline

August 2022: Unifor’s Constitutional Convention Delivers Mandate

In August of 2022, delegates to the Unifor Constitutional Convention endorsed the union’s 2022-2025 Action Plan. Among the commitments outlined in the plan is for the National Union to update its National Bargaining Program, and to ensure the Program is “informed through a cross-country engagement of Unifor local union leadership, bargaining committee representatives, activists and staff.”

December 2022: Working Group Launched

In December of 2022, Unifor’s National leadership invited various elected officers, National Executive Board members, and senior staff to participate in a Working Group that would oversee the National Bargaining Program update and local union engagement tour – under the project title: Bargaining Workers’ Power.

The Working Group was asked to provide input and guidance on the following items:

Organizing a cross-country engagement effort that is as inclusive and responsive as possible for Unifor members,

Ensuring that regional meetings are well-attended, and the programming yields meaningful dialogue and input,

Identifying key themes from regional meeting reports to help guide the design of the new bargaining program,

Reviewing and commenting on drafts of materials, as well as the bargaining program itself, and Developing the agenda of a National Bargaining Summit.

January-February 2023: Materials Developed

Over the course of January and February of 2023, a Bargaining Workers’ Power “discussion-starter” presentation was prepared by the Research and Education Departments, along with a set of three discussion questions. The presentation and questions were piloted at a special meeting of Unifor’s Northern Ontario local union leadership as well as a series of local union events as part of the Unifor Quebec Director’s Tour. Feedback from these pilot sessions informed Working Group final decisions on developing the structure of the Regional Strategy Sessions.

February 2023: Regional Strategy Sessions Promoted

Working Group members developed a list of targeted communities, dates, and venues for the Regional Strategy Sessions. Registration was facilitated through a dedicated Unifor webpage prepared by the Communications Department.

Outreach materials were sent from the National President’s office to staff and local union leadership. Additional outreach to locals was made through the offices of the Regional Directors, as well as direct communication to locals by the appropriate Area Director.

February-June 2023: Cross-Canada Regional Strategy Sessions Held

Between February and June of 2023, a series of 45 Regional Strategy Sessions were held in communities across the country with a high concentration of Unifor members, including two virtual sessions. One of the virtual sessions solicited input specifically from the members of Unifor’s Equity Standing Committees.

June 2023: Information and Member Input Gathered from Regional Sessions

During the Regional Strategy Sessions, Unifor researchers (or designates) took detailed notes of comments and issues raised by members. These notes were grouped together and analyzed with the help of a customized computer program developed in house.

The program helped identify issues and topics mentioned by members across the multiple strategy sessions, produced a list of the most talked about issues, and grouped members’ comments by those issues.

The goal was to produce a document that effectively captured and presents what we heard from members during the strategy sessions. This culminated in the interim What We Heard report, published in early July 2023.

July-August 2023: Final Report Prepared for Bargaining Summit

Informed by member priorities and ideas, a final Collective Bargaining Program report was prepared, including a series of specific bargaining directives and recommendations. This final report will be submitted for discussion at Unifor’s 2023 Bargaining Workers’ Power Summit.

Economic and Labour Market Climate for Workers

Since 2022, workers in Canada have found themselves in an uplifting but also puzzling economic climate. Historically low unemployment and high job vacancies means that most workers are in a stronger bargaining position than has been the case for many decades. However, the threat of recession brought about by reckless monetary policy in the fight against inflation, as well as various workplace restructuring and legislated wage restraint measures, leaves Canada’s strong economic recovery, following the COVID-19 pandemic, hanging in the balance.

The challenges confronted by workers over the past few years cannot be overstated. Not only did the pandemic create a public health emergency the likes of which most Canadians have never seen, it sparked an unprecedented economic crisis that was accompanied by the highest rates of unemployment since the 1980s. The subsequent economic recovery saw workers, particularly women and youth, re-enter the labour force in record numbers in 2022, which pushed unemployment rates down to historic lows.

At the same time, elevated inflation (also hitting highs not seen since the 1980s) and overly aggressive interest rate hikes by the Bank of Canada have eroded workers’ purchasing power and squeezed family budgets on essential items such as food, rent and travel. Yet, as workers paycheques get pinched, corporations in Canada reported record profits. In fact, workers are shouldering the burden of high interest rates to fight inflation even though they were never the cause to begin with.

The cost of living needs to be addressed. Our wages are not keeping up with the rising price of food, housing and other goods.

Halifax, April 19

In this uncertain environment, the Canadian economy continues to send mixed signals. Growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (a measure of economic activity) slowed to a halt towards the end of 2022 but was still higher than forecast. Inflation also fell to 3.4% in May 2023, year-over-year, after hitting a high of 8.1% the previous summer. Employment growth remained strong in the first half of 2023 but there have been signs that underlying labour market conditions are weakening, with job vacancies in early 2023 falling from their peak pandemic levels.

In short, Unifor members are confronted with a historic opportunity to wrest significant gains from their employers and to successfully bargain for a fair share of recent economic growth, which continues to accrue disproportionately to the wealthiest of Canadians. As always, however, these opportunities will inevitably shift with changing fortunes of the economy, which are currently in flux.

Employment

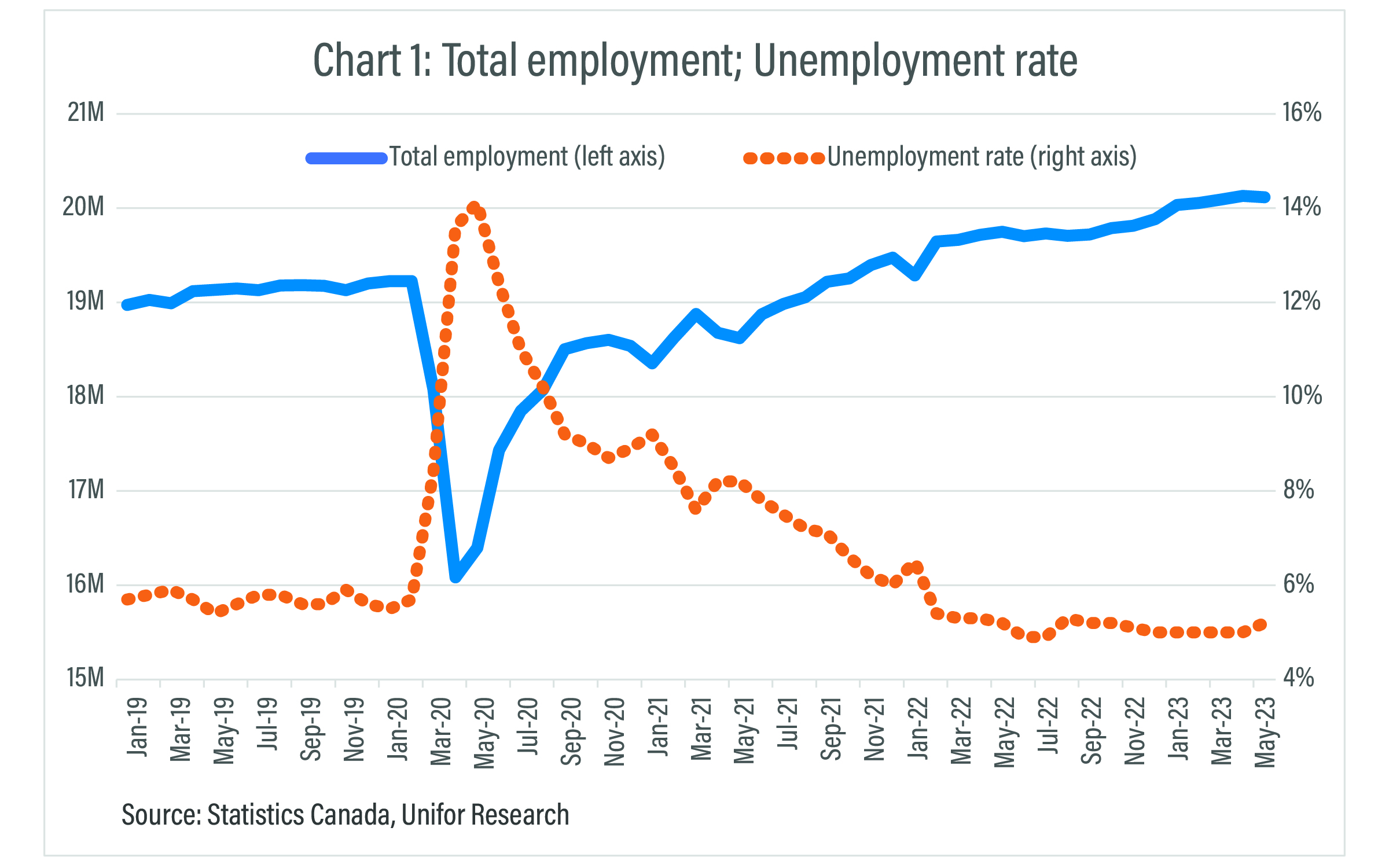

Canada’s job figures defied gravity during the first few months of 2023, with employment growth sustaining its unexpected surge from 2022. From June 2022 to April 2023 – a period when economic analysts repeatedly warned of an impending slowdown – the economy added more than 400,000 jobs. Despite a slight increase to 5.2% in May 2023, the unemployment rate stayed level at a near-record low of 5.0% for five full months, from December 2022 to April 2023.

The speed of the turnaround in labour market conditions from the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic has truly been staggering. Unemployment hit 14.1% in May 2020 – the highest level since comparable statistics became available in the 1970s. By June 2022, however, the unemployment rate had fallen to 4.9% and the number of jobs surpassed the pre-pandemic level by nearly half a million (see Chart 1).

To its credit, the federal government responded to both public health and economic emergencies with urgency and introduced a series of income security measures, including the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS), as well as a temporary expansion of the Employment Insurance (EI) program, that helped blunt the worst impacts of the pandemic on workers.

The reopening of the economy was accompanied by mass retirements in 2022. The number of retiring workers increasing by 32% compared to the previous year and job vacancies hit a record 1 million.

Sadly, calls by labour unions and worker advocates to make permanent improvements to Canada’s labour market supports, including EI reform and more transition supports for workers requiring retraining, fell on deaf ears. Employers were able to shift the labour policy conversation towards overwrought concerns about labour shortages instead of improving job quality to attract and retain workers.

Wages

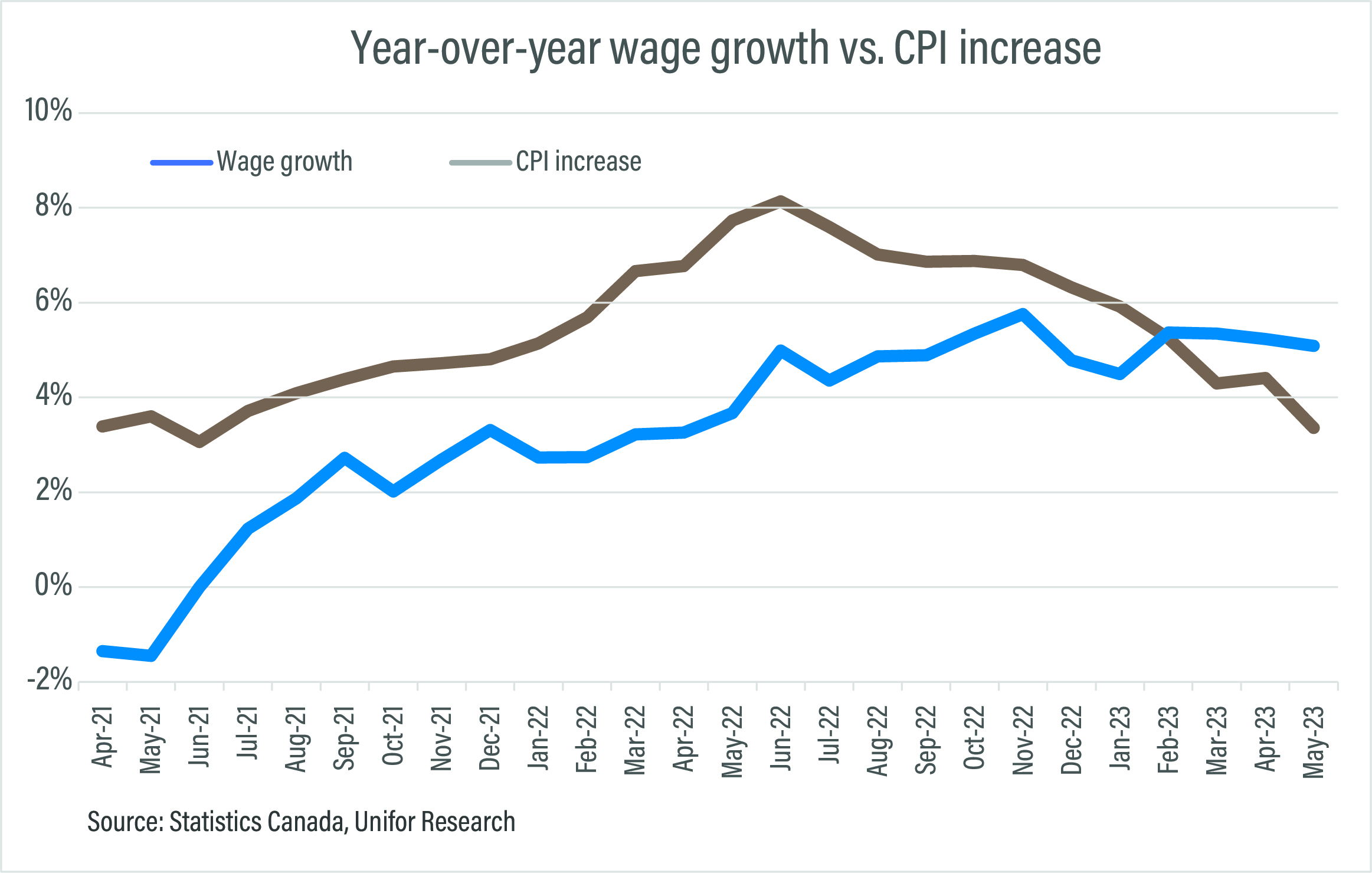

Although average nominal wage increases have been relatively strong since mid-2022, it was only in February 2023 that real, inflation-adjusted wage growth started to rise. Year-over-year wage growth fell below the rate of inflation in March 2021 and lagged for nearly two years before catching up in February 2023 (see Chart 2). In other words, for most of 2021 and 2022, the average worker in Canada saw their incomes fall behind the increased costs of consumer goods and services, with each dollar buying less than the month before. It remains to be seen whether workers can fully recover what was lost.

The decline in real wages during this period underscored the importance of unionized workers bargaining effective cost-of-living offsets into collective agreements, including Cost of Living Adjustments (or “COLA clauses”), many of which had been removed from collective bargaining agreements or indefinitely frozen, in part due to decades of low inflation.

Inflation

Policymakers, industry, workers, and consumers alike were all affected by a relatively sudden upswing in inflation during 2021, which was a global phenomenon. As Canada’s inflation rate soared to 8.1% in June 2022, many observers pointed to the significant disruptions that had occurred because of the COVID-19 pandemic, causing spikes in prices at various stages of the supply chain, as well as consumer goods and services. However, some conservative economists and politicians took to suggesting – without evidence – that the cause of the price rise was the financial relief provided by governments during the worst periods of the pandemic – the same programs that kept businesses solvent and workers with enough income to pay their bills.

In actuality, the rise in inflation was partly the result of pent-up consumer demand during pandemic lockdowns, soaring fuel and commodity prices and severe supply chain bottlenecks that occurred during the acute phase of the pandemic. These inflationary pressures were sustained as the war between Russia and Ukraine upended global food, feedstock, and gas supplies. Right when governments around the world should have been putting their plans to ‘Build Back Better’ into action, conventional monetary and fiscal responses to rising inflation were used to justify scuttling those plans.

Bullied into complacency by conservative policy makers and politicians, governments lowered their ambition and set their eyes upon a return to the pre-pandemic status quo. The Bank of Canada ratcheted up class warfare through aggressive monetary policies designed to increase unemployment, and blamed workers for inflationary pressures simply because they demanded a fair share of the economic recovery and to maintain their purchasing power.

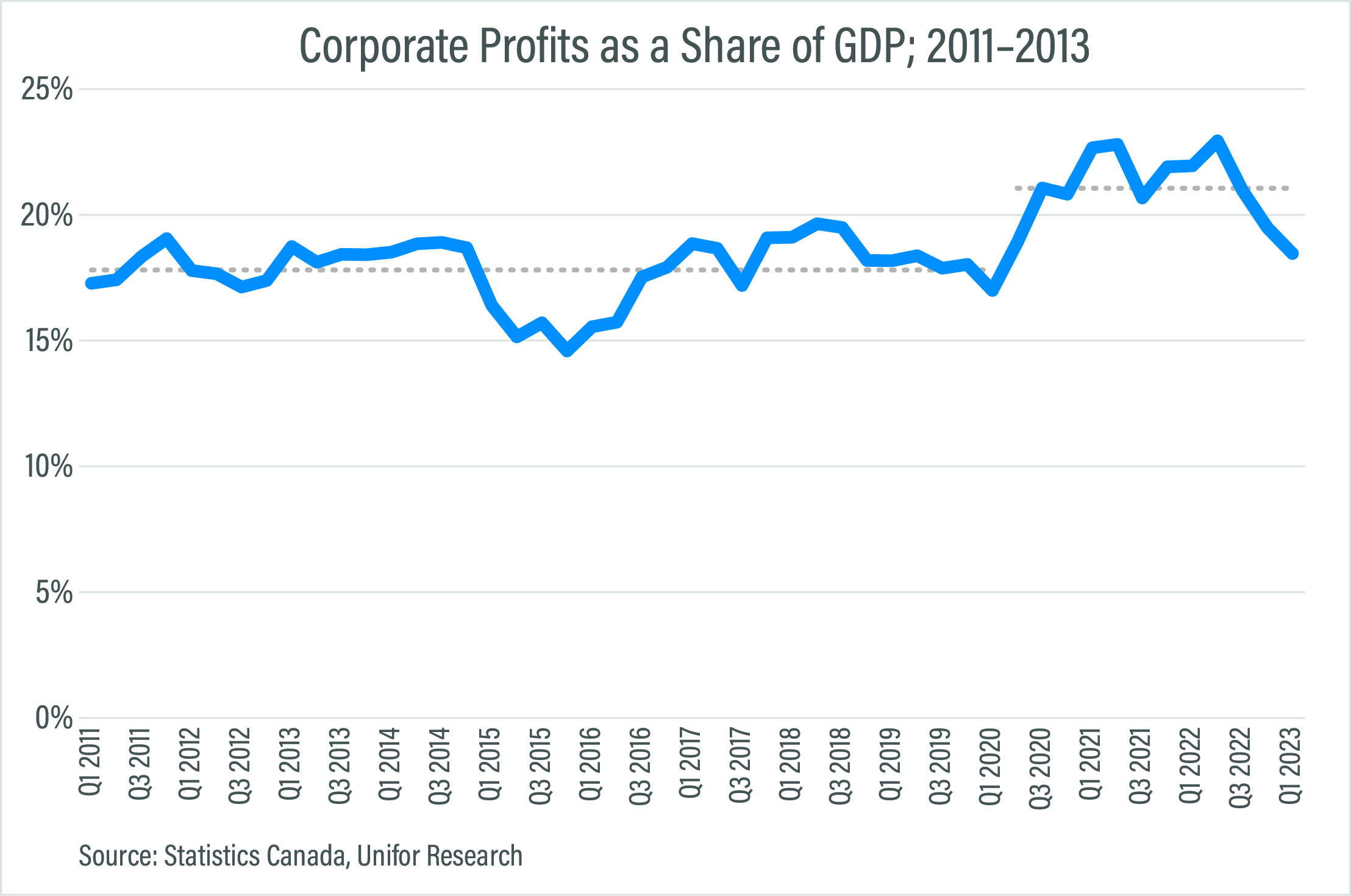

Meanwhile, under the cover of high inflation, corporations raised profit margins and continue to cry poor when workers come asking for higher wages to offset their loss in purchasing power. While profits as a share of GDP have been steadily rising for decades, they hit new heights during the pandemic. In the 8 years before the pandemic, profits as a share of GDP averaged 18% but have since soared to an average of 21% since Q2 2020.

Instead of heeding this data by training their sights on profiteering and highlighting the role of supply chain issues, the Bank of Canada began to preach that restraining wage growth and re-establishing a “sustainable” rate of unemployment was the best way to fight inflation. The Bank continues to raise interest rates and has shamelessly encouraged employers to limit wage increases, despite no evidence suggesting workers’ wages or low unemployment are playing an inflationary role.

Inclusivity/Human Rights

The calls to ‘Build Back Better’ after the pandemic included a drive to build more diverse workplaces, labour markets and institutions – fostering inclusive economic growth. For a short time, there was hope that, at least in Canada, government and employers would work with labour and community to make our economy more inclusive and equitable.

In the context of high vacancy rates and low unemployment, many saw an opportunity to increase labour market participation and dramatically improve the employment outcomes of equity deserving groups.

For example, people with disabilities and their allies advocated for employers to become more attentive to accessibility needs to end the needless exclusion of thousands of people from working in this country, thus growing the labour market.

At the same time, Statistics Canada began collecting and reporting labour market data disaggregated by race and new efforts to understand gender diversity and the prominence of 2SLGBTQIA+ identified people in the workforce were undertaken. More data has only further confirmed that systemic racism, sexism and anti-2SLGBTQIA+ discrimination continuously leads to unequitable labour market outcomes leaving Black, Indigenous and Workers of Colour, women, and workers from the 2SLGBTQIA+ community with less income and poorer working conditions than their white and male peers. These workers also face discrimination and harassment in the workplace that needlessly make work and life more stressful.

Rather than working to increase job quality, decrease discrimination and increase accessibility and employment security, employers successfully lobbied government to increase the supply of insecure labour through the immigration pathways that most often leads to poverty and exploitation.

Now, and in the coming years, our union must remain vigilant and confront the presence of xenophobic, racist, sexist, able-ist and anti-2SLGBTQIA+ views, building workplaces that are safe and welcoming places for everyone.

Climate change/industrial transition

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic was followed by a brief respite in the pace of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions growth due to the sudden global economic slowdown. In the ensuing years, the environmental and economic challenges of climate change quickly reasserted themselves and will likely worsen in the coming years. Canada has experienced unprecedented climate disasters, with record-breaking wildfires and flooding becoming an annual occurrence.

While governments at the federal and provincial levels have largely abandoned their more ambitious recovery plans, one piece of the ‘Build Back Better’ agenda that has seen real activity is the push for a transition towards a greener, decarbonized economy. At the federal level, the government has earmarked $60 billion in tax credits over the next decade to support and entice large and medium sized corporations to reduce emissions through clean technology and green hydrogen investments.

In the auto industry, government has invested billions to assist in the transition to electric vehicles by investing in manufacturing as well as charging infrastructure. Government must build on these efforts and expand the industrial strategy framework across the entire economy.

Meanwhile, technological change is constantly nipping at the heels of workers. Artificial intelligence, autonomous vehicles, invasive surveillance, and the digitization of everything from records to currencies are just a few broad categories of technology that threaten to dramatically alter or even eliminate the jobs of thousands of workers across the country.

It is in the context of these accelerating changes that federal and provincial governments need to build concrete transition supports for workers and a more ambitious industrial strategy that coherently integrates and coordinates government support for investments in energy, auto, transportation, critical minerals, and so on.

In this context, more and more locals across Unifor have signalled their intent to bargain for transition- and technology-related language and protections within their collective agreements.

Conclusion

The multifaceted economic challenges and opportunities laid out above highlight the need for a national bargaining strategy that is both wide-ranging in the kinds of issues addressed and capable of targeting several structural labour market challenges confronting workers. The program must be bold, ambitious as well as relevant and accessible to members. It must be intersectional and recognize the differential impacts of these challenges on workers who are women, Indigenous, BIPOC, migrants, 2SLGBTQIA+ and/or have disabilities, whose lived experiences of the pandemic and subsequent recovery were far more difficult than others. Fortunately, the invaluable grassroots input of Unifor members throughout the consultation sessions has laid a clear path to address these issues and helped to identify the main bargaining priorities moving forward.

Priority Issues and Union Positions

Wages and Income Security

Despite Canada’s record-breaking recovery following the COVID-19 pandemic, economic uncertainty persists for workers. From coast to coast to coast, workers struggle with rising prices while fearing a major economic slowdown. Inflation remains persistently high, with no guarantees of a return to the stable and steady price increases we have seen in recent decades. Groceries, fuel, and housing costs continue to increase – eating away at the real value of workers’ incomes. Governments that heeded long-standing calls from labour unions and worker advocates to adjust minimum wages to inflation have kept hundreds of thousands of vulnerable workers out of poverty. At the same time, and for many middle-income workers, such cost-of-living offsets (including COLA clauses) have become increasingly rare. Fewer collective agreements have active COLA provisions today than in decades past. The same is true with pension plans that are less likely to provide benefits indexed to inflation.

Compounding this problem is the economic and job uncertainty facing Unifor members in vulnerable or transitioning sectors, including media, manufacturing, forestry, energy, transportation, and many others.

Job security and income protection provisions in collective agreements are under attack. Employers continue to claw back key provisions like access to benefits during periods of layoff, and severance provisions. At the same time, supplemental measures like income top-ups and payments for EI waiting periods are becoming harder to achieve. And although important progress has been made to advance pay equity, gaps persist. There is much more work to do, particularly for racialized and Indigenous workers, workers with exceptionalities, and members of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community.

Across the Regional Strategy Sessions, there were notable differences of opinion between members about wage and income security. Some saw the need to prioritize immediate pay increases over retirement savings and benefits. Others expressed frustration at their employers’ refusal to eliminate two-tier wage structures or exceptionally lengthy grow-in periods, especially when facing a tight labour market and worker retention challenges. Others saw value in cutting back on workhours, creating job security for younger workers, as well as enhancing pension income benefits.

Bargaining Priorities for wages and income security

Despite the struggles of many Unifor members, corporate profits continue to grow. CEO’s continue to give themselves large bonuses and increase their own pay rates while blaming workers and their demands for higher wages for rising prices. In today’s tight labour market, workers not only have the opportunity but the responsibility to negotiate higher wages and earnings, that account for the rising cost of living as well as soaring profits. Workers also must focus attention on improving income offsets supports during periods of layoff, workplace transitions, and leaves of absence.

There are many mental health challenges faced by members in our workplaces. Currently, we just get a small pamphlet of information from the employer. If we negotiated resources, and outlined them, in the collective agreement, members can have the privacy to seek out support on their own without having to ask and risk being stigmatized at work.

Halifax, April 19

Unifor will:

- Negotiate market adjustments and pay increases commensurate with the rate of inflation. Unifor will strive to bargain provisions that guard wages against rising prices and other inflationary pressures. This may include new or reactivated Cost of Living Adjustment (COLA) clauses, special payments, improvements to meal or travel allowances or automatic pay scale adjustments, as well as provisions to safeguard retirement benefits, among other potential measures.

- Negotiate pay equity into collective agreements and hold employers accountable to their legal obligations. We must continue to negotiate pay equity into our agreements to reduce the gender wage gap and other gender-based pay disparities. Where pay equity legislation exists, we must ensure employers are meeting their legal obligations. This includes forming the necessary workplace committees, developing concrete plans, processes and timelines towards pay equity implementation, and regular monitoring and evaluation.

- Recognize and address pay differences in equity-deserving groups. We must recognize and address the pay differences that continue to devalue work performed by Indigenous workers, young workers, workers with disabilities and workers of colour.

- Seek to eliminate arbitrary pay scales, wage grow-ins, and reject two-tier wages. Employers continue to rely on unjustifiably lengthy pay scales for new hires, decoupled from any reasonable training and development requirements, or other workplace considerations (i.e. investment preconditions). In these cases, the union will seek to eliminate such scales or significantly shorten them to a justifiable length. Further, where permanent two-tier wage provisions exist, the union will seek to bargain wage harmonization.

- Reject management proposals for future tiers. In addition to seeking the consolidation of wage tiers, Unifor shall not accept or entertain any management proposal for contract wage tiers. Staff is instructed to notify the National President’s Office of any such request that is presented at the bargaining table.

- Negotiate improvements to base rates of pay and avoid contingent, performance-based, or other variable pay schemes where possible. Ensuring that pay raises are reflected in a worker’s hourly or salaried base rates of pay often yields the greatest earnings. Base rates have a beneficial ‘roll-up’ effect – in other words, as base rates increase, the value of other wage-related benefits workers enjoy, including vacation, holiday, overtime, and others increase as well. Conversely, variable forms of pay (performance bonuses, profit-sharing, piece rates, recognition payments, for example) are widely supported by employers. These pay schemes are typically based on arbitrary measures (determined by the employer) and provide only temporary, time-limited benefit. Bargaining committees must exercise caution if such contingent pay proposals are tabled by employers. Committees are encouraged to focus on base rate improvements to pay, wherever possible.

- Negotiate appropriate income security and salary maintenance provisions to offset members’ lost earnings due to layoff or leave of absence. Such provisions might include a registered Supplemental Unemployment Benefit (SUB) programs, income top-ups, pre-retirement income bridging, or supplemental payments to workers on maternity, parental (including adoption) or caregiving leave (including compassionate care).

- Bargain minimum wage “escalator” provisions. Various governments have, in recent years, instituted automatic adjustments to minimum wage rates – a useful policy to ensure the legislated wage floor does not fall below rate of inflation. Our union will seek to negotiate minimum wage ‘escalator’ provisions, where feasible, including so-called “Minimum Wage Plus” provisions, to ensure that negotiated rates of pay stay proportionally above minimum wage.

When workers feel undervalued this leads to mental health challenges, and extremely low workplace morale.

Winnipeg, May 24

Health and Safety

Helping to ensure the health and safety of workers is one of the most critical bargaining priorities that labour unions must contend with.

Unifor members are confronted with workplaces that pose real risks, not only to their physical health and safety through potentially hazardous job tasks and responsibilities, but increasingly to their mental health and well-being as employer demands for increased productivity ramp up. A 2021 survey by Mental Health Research Canada found that one-third of Canadian workers were experiencing burnout at work, a figure which increased to 41% of workers of colour, 43% of members of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, 52% of those with existing mental health impairments, and 46% of those with chronic pain or a physical impairment; however, just 30% of workplaces have a mental health strategy in place. It is no surprise that Unifor members identified mental health as among their top workplace concerns, throughout the union’s Regional Strategy Sessions.

The COVID-19 pandemic also revealed that most workplaces were not adequately prepared for a public health emergency and did not have sufficient health and safety mechanisms in place to prevent the transmission of a highly infectious disease. Many Unifor members became ill and some even tragically lost their lives due to the absence of needed transmission mitigation measures, personal protective equipment (PPE), and outright negligence by employers. Oftentimes, it was local union representatives who became the primary advocates for emergency health and safety policies and procedures to ensure that workers were protected.

A shifting climate and increasingly extreme weather patterns are also changing the way that workers work, especially in parts of the country that are at heightened risk of heatwaves, fires and flooding. In addition to traditional stressors as well as health and safety hazards that arise within the workplace, joint health and safety committees must now tackle environmental and climate-related hazards that often prove to be unpredictable.

Bargaining Priorities for Health and Safety

As workplaces and working conditions evolve, we will need to update our bargaining priorities to ensure that workers do not face undue health and safety risks while performing their jobs. Many health and safety challenges were identified by Unifor members across the country as pressing concerns that need to be addressed through strategic bargaining, including primary prevention and accessing effective mental health supports, with targeted supports for workers with disabilities, workers of colour and 2SLGBTQIA+ workers; the need for mental health advocates in the workplace; protecting workers during public health emergencies; addressing detrimental impacts of technological change; and improving health care and mental health benefits.

Unifor will:

- Bargain adoption of the Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace Standard. We will strive to negotiate CSA Z1003 Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace Standard to identify psychosocial hazards in the workplace that may cause or contribute to mental health impairments and implement proactive preventative measures to eliminate them or reduce effects of all psychosocial hazards.

- Guard against the use of Behaviour Based Safety programs. Our union will develop and negotiate language that eliminates Behaviour Based Safety (BBS) programs and any other employer programs that seek to incorporate ‘resilience’ training as a response to health and safety issues, including mental health challenges.

- Negotiate workplace-based Workers’ Compensation Representatives and Mental Health Advocates. Such representatives shall be trained to assist members on all relevant matters and referrals. The union must also require that current and future Health, Safety and Environment representatives and advocates undergo employer-funded training to understand the unique challenges faced by workers with disabilities, workers of colour, and 2SLGBTQIA+ workers.

- Negotiate workplace training and oversight of time-based production standards and excessive workloads. Our union must exert influence over employer methods of workplace ‘speed-up’, excessive workloads as well as sophisticated models of engineered work standards, including through oversight and employer-provided training, to mitigate health and safety risks and disciplinary actions.

- Bargain strong “working alone” provisions. We will negotiate clear provisions that ensure members are not required to work alone or in isolation, wherever possible. In circumstances where working alone is unavoidable, even for short periods of time, our collective agreements must ensure that comprehensive hazard assessments are conducted jointly (between management and the union) resulting in proactive preventative measures to address all hazards, as well as the development of safe work protocols.

- Bargain pandemic preparedness plans. Our union will seek to negotiate contract clauses and protocols with the employer that address health and safety hazards in advance of public health emergencies.

- Bargain climate-related hazard assessments. We will negotiate the inclusion of mandatory climate- and weather-related hazard assessments into collective agreements, within the purview of Joint Health and Safety Committee responsibilities.

- Negotiate safe washrooms and supportive spaces. The creation of safe washrooms and supportive spaces for 2SLBTQI+ members who are experiencing a marked increase in harassment and abuse, supported by the use of gender-neutral language, wherever appropriate.

- Bargain a minimum of 40 hours of paid HSE training. The union will seek to negotiate a minimum of 40 hours of paid HSE training into our collective agreements, with provisions for all union health and safety representatives and/or JHSC members to access the training.

- Negotiate enhanced life insurance benefits for families of workers killed on the job and mandatory inquest. The union shall seek to negotiate an improvement factor of 5-times annual income as a standard life insurance benefit for dependents of workers killed on the job. The union will also seek to negotiate employer obligations to agree to family or union demands for an inquest if a member is killed in the workplace or dies from a work-related illness.

- Bargain restrictions on the use of mandatory overtime. To better encourage work-life balance, control over work time, and to incentivize job creation, the union will strive to negotiate overtime provisions that are voluntary for members.

Benefits

Benefits and mental health support were key areas of concern for members, second only to wages in terms of priority items raised in the Regional Strategy Sessions.

We have to end all discriminatory measures related to pension funds.

ste-Therese, March 21

Like all other goods and services, the cost of workplace health and related benefits has increased in recent years. Members who co-fund their plans are seeing larger increases being taken off their pay cheque each year. Short and long-term disability premiums, for instance, have sky-rocketed. As one Unifor member from Edmonton described, right now, those who make the least pay a larger share of their income to just maintain the current level of benefits.

Within our membership, there is a divide about prioritizing enhanced benefits and lower premium rates over general wage increases. This makes it difficult to advance and prioritize benefits gains when at the bargaining table.

Despite increasing costs, many plans don’t necessarily provide the coverage our members are looking for. For example, many plans exclude gender-affirming prescriptions and surgeries, meaning some of our members are not able to access medical services and supports needed to facilitate this life-changing transition.

Accessing benefits is becoming more difficult with the growth of the temporary, casual, and part-time workforce. Most benefit plans are only available to permanent and full-time employees. As a result, those who are in the most precarious positions are often excluded from participating, and must pay out-of-pocket for drugs, paramedical services, and dental work.

Burnout is becoming more and more common amongst members. Increased rates of workplace violence, harassment, and verbal abuse, particularly for workers in public-facing jobs, is making it harder to show up for shifts with each passing each day. Benefits that are accessible and affordable become a lifeline to workers in need but appear further out of reach for many.

Bargaining Priorities for Benefits

Economic uncertainty and increased workloads are only exacerbating rates of burnout. Figuring out how to keep up with the rising cost of goods and services is a massive source of stress for many. At the same time, workers are being asked to work longer, harder and faster than they ever have before to offset high job vacancy rates. Very few Unifor members felt their contracts had adequate coverage for mental health leave. Lack of adequate paid time off away from work to rest and recuperate was a common theme across all Regional Strategy Sessions.

Enhanced benefits are a hard-fought victory for union workers. We must strive to protect what we’ve got, build on what we have achieved and improve access to this very important part of a compensation package.

Unifor will:

- Bargain workplace group benefit plans. The union must prioritize the negotiation of workplace group benefits plans, where none exist currently.

- Bargain improved access to existing health benefits. Bargaining language that enables more part-time, casual, temporary and seasonal workers to participate in health plans is essential and should be explored in every round of contract negotiations. A specific focus in bargaining must also be applied to active workers who are older than 65 and ineligible for benefits.

- Ensure all collective agreements have gender affirmation provisions enshrined in the benefit plan. This includes drugs, surgical coverage and mental health support at all stages.

- Bargain enhanced leave provisions that enable members to use sick time for mental health. Ensuring that members have adequate paid time off from work to rest and recover from periods of burnout must remain a top priority at every bargaining table. We will continue to push for more vacation time, paid time off for personal reasons, and the extension of sick leave to our part-time and casual members.

- Negotiate higher employer contribution rates for benefits. As premiums increase, especially as increasing public health care costs are downloaded onto private benefit plans, we will resist cost shifting from employers and instead push for higher employer contribution rates in contracts where benefits are co-funded to cut down on the out-of-pocket expense to our members. This can include provisions for automatic indexing of employer contributions to match rising premium rates. We will bargain paramedical and dental coverage increases in relation to the cost of the services performed.

Any workers in a Unifor-represented workplace must receive the full benefit of the collective agreement. That includes temporary workers, contract workers or migrant workers. We all deserve similar rights and protections on the job.

Durham, May 29

- Bargain provisions applicable to the needs of young workers’ and young families. It is important to prioritize benefit provisions that are responsive to the needs of young workers and members with young families. This can include provisions for paid leaves for stillbirths, parental, caregiver and sick leave benefits, income top-ups and Supplemental Unemployment Benefits during periods of layoffs, as well as guaranteed work hour provisions.

- Negotiate paid leave entitlements for all workers. This includes paid personal days, paid emergency days, sick leave, programs, deferred salary leave, sabbatical and education leave, extended bereavement leaves, parental leaves and others.

- Bargain group benefit extensions for workers facing workplace closures. This shall apply to any enhanced severance package as well as during extended layoff periods, and during public health emergencies.

- Negotiate improvements to short-and-long term disability benefits. Bargaining committees can consider proposals that require employers pay the full cost of insurance premiums for STD and LTD benefits and negotiate provisions that ensure such benefits keep pace with both negotiated pay increases, rising consumer prices as well as recognize service eligibility for pension based on deemed earnings. The full cost of any employee portion related to pension contributions must also be paid by the employer on a mandatory basis during periods of disability. Where possible, the union shall guide the design and administration of STD and LTD plans, informing what is considered fair and reasonable return to work practices, accommodations, among other provisions specific to the bargaining unit.

- Protect health care benefits for retired workers. The union will ensure, wherever possible, that retired workers retain access to a level of necessary health and medical benefits that supplement publicly funded programs.

Pensions and Retirement Security

Workplace pension plans must become the norm for workers, once again, rather than the exception. Our union’s negotiating position must be to bargain new pension entitlements where none currently exist in our collective agreements. We must also enhance pension coverage for all workers where these entitlements are already bargained. Together with strong public pensions like the Canada and Quebec Pension Plans, Unifor must ensure that our members retire with secure and adequate lifetime income.

Far too many workers, including active Unifor members, have inadequate or no access to a workplace pension plan. This is particularly true in highly precarious and low-wage sectors of the economy, including service industries where equity-deserving groups form a dominant portion of the workforce. This is a worrying trend that will likely grow into a larger societal problem of wealth disparity and polarization, as fewer retirees are able to maintain a decent standard of living with very little or no workplace pension to depend upon.

Employer-sponsored Defined Benefit pensions plans, the gold standard and most dependable retirement arrangements for workers, have always been at the forefront at bargaining discussions. Unifor has done an admirable job defending and protecting our members wherever these entitlements are threatened – although not all fights have ended in success. Less dependable retirement income plans such as Defined Contribution pension plans and Registered Retirement Savings Plans (or where members have no retirement security at all), require our collective scrutiny and review. The union must evaluate its bargaining strategies around pensions, in the current economic context, to best protect the retirement interests of our members.

As new technology advances so does employer surveillance over workers, often resulting in discipline. The union has to do more to guard against unfair and unreasonable monitor and personal privacy.

Charlottetown, May 8

Recent government enhancements to the CPP and QPP are welcome, but not enough. Simply put, those that devoted their working lives and contributed to the success of Canada’s economic prosperity deserve to retire with dignity.

At each Regional Strategy Session, Unifor members spoke loudly about their concerns that retirement benefits are being diminished, both by employers as well as clawed back by rising inflation. While it is a significant challenge (and cost to active workers) to reverse decades of pension erosion, it is incumbent upon the union to explore innovative alternatives to bolster pensions and retirement security, wherever possible. We must strategically re-examine our role into the future around sustainable workplace pension models. Presuming that corporations and the financial industry will come to the rescue for working Canadians at retirement, is a risk we simply cannot afford to take. With collective action and a solidarity mindset, we must avoid falling prey to the narrative perpetuated by profit seeking enterprises that workplace pensions are too expensive to bear.

Unifor BWP Map

Bargaining Priorities for Pensions and Retirement Security

Despite the obvious downward trend in registered Defined Benefit pensions across Canada, these plans remain an important piece of Canada’s retirement landscape for tens of thousands of Unifor members and must be defended at all costs. As interest rates rise, so too does the attractiveness of Defined Benefit or Defined Benefit-modelled plans. There is an opportunity for the union to reinforce pensions and retirement security as a priority issue at bargaining tables.

Unifor will:

- Bargain new workplace pension plans, and defend and enhance existing plans, wherever possible. As workers exert bargaining influence in sectors where job recruitment and retention is a challenge for employers, and where profits are rising, a strong case can be made to both introduce new and bolster existing pension plans.

- Negotiate the removal of caps on credited service. In single employer Defined Benefit pension plans, the union will seek to enhance retirement income through the pension plan.

- Embrace innovative pension models that yield greater benefit to members. Multi-employer and union-sponsored target pension plans can yield predictable lifetime income that is far superior to existing Defined Contribution plans. The union shall explore these wherever feasible.

- Negotiate more accessible pension plan qualifying rules. Members, including those working in low-wage sectors, may have a registered pension plan available to them but cannot qualify for entry into the plan. This creates very particular challenges for equity-deserving groups, like women and workers of colour, disproportionately represented in part-time, precarious jobs. The union must seek to improve pension plan access in all circumstances.

- Expand access to retirement and financial planning workshops. The union can negotiate access to employer-sponsored training for members nearing retirement or other financial literacy tools, to assist in their personal planning and enable them to make informed decisions about life after work.

- Continue to negotiate living standard improvements for retired workers. Our union has, in various instances, undertaken to negotiate enhanced benefits for retirees and their surviving dependents. This is an act of inter-generational solidarity and must continue, where possible.

- Ensure pension plan surplus funds benefit plan members. Employers must not be allowed to use pension plan surpluses to pay for other financial obligations or for any reason, without express agreement of workers. Surpluses must only be used to improve and secure the retirement security of plan members.

Human Rights, Inclusion, and Workplace Equity

Systemic inequality is a persistent feature of the world of work. Equity-deserving members continue to experience discrimination, exclusion, and injustice in their workplaces. Hard-fought gains are often too limited and substantive equality and workplace justice feel further away as our equity-deserving members experience worsening conditions and mistreatment at work.

The individual lived experiences of our members, highlighted throughout cross-country Regional Strategy Sessions, too frequently reflect systemic problems in our workplaces. The gender wage gap endures. Unemployment, underemployment, and low wages continue to disproportionately impact Indigenous, Black and workers of colour, 2SLGBTQIA+ workers, young workers, and those with disabilities. Those with intersecting identities face even more significant barriers when seeking and retaining employment.

To address these ongoing challenges, Unifor must bargain provisions that directly respond to workplace discrimination and racism. Effective bargaining strategies also need to apply an equity lens to all proposals and existing provisions to ensure that marginalized workers, who often face additional barriers in employment, are not left behind in our demands for meaningful workplace justice for every member. Attention must be paid to the needs of new Canadians and immigrants who may have little experience with unions and may have language barriers that impact opportunities within the workplace and the union, including in Quebec and other predominant French-speaking communities throughout the country.

We need guarantees from the companies that we are part of their transition plans, and that we are attached to the potential new jobs that will be created.

Edmonton, May 16

Local Union leadership and bargaining committees that reflect the diversity of the membership are better positioned to assert demands that reflect the needs of all leading into and throughout the bargaining process.

Our negotiations at the bargaining table in respect to human rights and equity are also influencing our advocacy outside of the workplace. We continue to voice demands to address serious issues like reproductive, racial and disability justice, Truth and Reconciliation, and the safety of members of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community. Unifor remains active in the public sphere on behalf of all workers not just those who have secured the benefit of unionisation.

Bargaining Priorities for Human Rights, Inclusion, and Workplace Equity

To support discrimination-free and inclusive workplaces where all workers can thrive, Unifor will build upon our previous bargaining program and successes and focus on the following bargaining priorities:

Unifor will:

- Negotiate employment equity language into collective agreements. Negotiated employment equity provisions must address targeted hiring, retention, and advancement of underrepresented groups. including women in male-dominated workplaces and trades.

- Ensure the collection of membership demographics and encourage workplace equity audits. The collection of demographic information and commitment to engage in workplace equity audits will ensure that targeted programming and supports meet the needs of members and those who have been traditionally underrepresented in the workplace.

- Negotiate workplace advocacy programs. Our union must commit to expand our Women’s Advocate and Racial Justice Advocate programs and bargain not just the position, but adequate time to learn and perform the roles.

- Bargain targeted leave provisions to broaden workplace inclusivity and equity needs and access to resources. Our union must consider comprehensive leave provisions to adequately support the range of equity needs, including such leaves as those for Indigenous practices, cultural holidays, francization leaves in Quebec, longer leaves for those with immediate family living abroad, gender affirming procedures, menstrual leave, and other reproductive health leaves, will better reflect the realities of more of our members.

- Negotiate better access to francization programs and resources in the workplace, with paid leaves to complete coursework. In Québec, being able to work in French is a right and our union must play a significant role to ensure training programs in the workplace are accessible, properly resourced and adapted to our members needs.

- Integrate Unifor’s long-standing commitments toward Truth and Reconciliation through bargaining and workplace practices. Our union will support Truth and Reconciliation in our workplaces through land acknowledgements, opportunities for training and by encouraging Indigenous voices in our workplaces, in the union and in activist spaces.

- Bargain anti-oppression training. Our union will seek to negotiate anti-oppression training for our members and for management to support equity seeking members, and to create opportunities for learning as our workplaces and jobs become populated by people of diverse backgrounds and lived experiences.

New Technology, Climate Change, and the Future of Work

Workers across the country will encounter job changes related to climate change, decarbonization or new technology. In some cases, workers will face these intersecting challenges all at once.

Responses to the climate crisis and biodiversity protection are growing in both scope and magnitude, as entire industries ready themselves to transform to lessen their impact on the environment. As in most cases, workers stand to shoulder the heaviest burden through job transformations, training needs and threats of job displacement.

Throughout the cross-Canada Regional Strategy Sessions, Unifor members shared their direct experiences with workplace technological changes related to decarbonization (including the shift to EVs happening in the auto sector), invasive surveillance, artificial intelligence and big data. Unsurprisingly, members characterized these experiences as a mixture of hope and fear: hope that there are future jobs and shared economic prosperity; but fear that employers will use this transformation to weaken work standards, cut jobs, and neglect workers’ needs.

In the transportation sector, for instance, many workers are facing constant, invasive surveillance that affects their autonomy on the job and their mental health. In the energy sector, decarbonization policies are forcing employers to implement emissions-reducing technologies in their operations while simultaneously investing in alternative energy sources for the future. In telecommunications, new technologies are facilitating the outsourcing of good, union jobs. In the media sector, artificial intelligence is directly threatening the jobs of reporters and, by extension, the quality of journalism. In the forestry sector, the challenge of protecting biodiversity has been front and centre across the country. Forestry workers must have a say in how the protection is rolled out so that they can help to shape the industry for the decades ahead.

Tech-induced workplace changes are nothing new to workers in Canada. We have seen the negative effects these technologies can have, absent proper oversight and regulation. Employers will use these periods of transformation to erode job quality, redefine skills and undermine and attack the union. Technologies, owned and managed by the boss, are primarily tools to increase profits, regardless of their effects on society.

There is no stopping technological advances and innovations from reshaping our work. In truth, not all change is bad. In some cases, it is desirable. What is critical is that workers have a say in how technologies are deployed, how they are managed and how they are monitored. Workers must reap the benefits of new technology and avoid its hazards. Done strategically, collective bargaining can provide a critical pathway for workers to manage workplace transitions and maintain decent, good-paying unionized jobs.

Limited housing supply, lack of access to services, the attraction retention challenge is more intense in remote communities.

Baie-Comeau, February 15

Bargaining Priorities for New Technology, Climate Change, and the Future of Work

Our goal is to harness the opportunities and mitigate the risks presented by these economic transitions.

Workers must be involved in transition discussions, whether through local risk assessments, retraining and retooling requirements, or advocating for both targeted and broad-based investments and supports. Industrial transitions triggered by climate change, decarbonization or new technology must be about building the industries of tomorrow, and clearly situating workers’ place within it - seizing the opportunities to strengthen our workplaces as the economy transforms.

Workers have had to fight to have a say in critical workplace issues for generations. Workers will have to fight for the right to shape upcoming workplace transitions, too.

Unifor will:

- Negotiate joint committees to manage workplace transition. Jointly managed committees can enable workers to tackle decarbonization and technological change in the workplace through a more formal and structured system of dialogue, and with greater transparency and information-sharing between parties.

- Require employers to notify the union of workplace technological adoption. Employers must be required to notify the union of forthcoming technological or operational changes and discuss their implementation.

- Secure training, upskilling and transition supports. Employer sponsored training, upskilling and enhanced income supports to assist workers during downtime must be negotiated and detailed in collective agreements. These provisions should be used to avoid permanent layoff and job displacement, wherever possible.

- Extend union coverage, through expanded scope clauses, neutrality covenants and voluntary recognition agreements, to new hires resulting from technological change and decarbonization efforts. This should include work done by contracting firms as well as joint ventures.

- Protect data privacy and use rights. Bargaining committees must negotiate clear limits on how data collected by employers can and cannot be used, for performance evaluation purposes but also by third party service providers. Language must lay out data privacy requirements as well as employer data storage safety protocols.

- Update job classifications to reflect new skills requirements, while protecting existing scopes of practice for skilled trades workers. Workers’ pay and benefits must evolve with rapidly increasing skills requirements in the face of technological change. However, negotiating an extension of skill requirements for classifications must guard against excessive workloads and must also preserve the integrity of the scopes of practices for certified trades.

- Bargain ‘Right to disconnect’ language. Unions must ensure workers can disconnect from work and to be paid when they are required to stay on call.

Workforce Attraction and Retention

The COVID pandemic had a major impact on Canada’s labour market, driving job vacancy rates to record levels. Some key drivers of these labour shortages are decreased immigration during pandemic lockdowns, a massive increase in career changes by workers in hard-hit sectors (sometimes referred to as the “great migration”), and a workforce that was already ageing rapidly before the pandemic.

Labour shortages are more pronounced in some sectors than others, based on the nature of the work, the required certifications and skill levels, job quality (wages and benefits, hours of work, working conditions), and where the jobs are located. At the same time, high job vacancy rates in some sectors are evidence of a “good jobs shortage” rather than a labour shortage.

As more workers become willing to change jobs and even careers in the hunt for better work, employers have to face a new set of challenges in terms of attracting and retaining talent. The new generation of workers are demanding more work-life balance, options for working from home, stable scheduling and hours of work, and access to full-time jobs. Canada is already home to a diverse population of workers, that is expected to grow even more diverse in the coming years. Employers will be expected to foster more inclusive, supportive, and accommodating workplaces not only to provide equal opportunities and good jobs for equity-deserving groups, but to tap into a labour pool with in-demand skills, knowledge, and experiences.

There’s a greater push by employers to hire new workers, and they’re reaching out to staff agencies. We need to use our own local unions to support hiring and reskilling workers into new jobs, especially in industries that are transitioning.

Windsor, April 3

These issues are now central to recruitment and retention in any workplace, and among the top-listed priorities issues for Unifor members across Canada.

Bargaining Priorities for Workforce Attraction and Retention

Some employers have responded to labour shortages by improving wages and benefits, introducing flexible work arrangements including working from home, creating more flexibility in scheduling to improve work life balance, and providing more training and skill development opportunities. Unfortunately, other employers have accepted and even embraced high turnover rates, leading to unsustainable workload levels for remaining employees and reducing the quality of the work environment.

New and young workers have different priorities than older generations of workers, and these priorities should be reflected in collective agreements and in the work of the union. While good pay, benefits, and job stability are still priorities, work-life balance is a major issue for new and younger workers. In addition, holiday allocation and inflexible shift schedules are identified by young workers as major friction points and often trigger job movement. Employers must focus on recruitment and retention rather than accept employee churn as a new fact of life.

Unifor’s bargaining priorities must include measures that address these recruitment and retention issues. Some options include work from home programs (where feasible), flexible scheduling and vacation allotment, and provisions that create training opportunities and development pathways for workers.

Unifor will:

- Develop and strengthen contract language regarding training and skill development opportunities and emphasize the need to develop career pathways. New and younger workers are more likely to stay at a job when they can see a clear path forward in terms of promotion and career development.

- Look for opportunities to implement or strengthen working from home programs, where feasible. Any working from home program must stay within the parameters of the collective agreement, must remain voluntary, and must improve flexibility for workers. Working from home programs should also protect worker privacy, and they must ensure workers do not shoulder out-of-pocket expenses. In addition, the union must secure outsourcing bans or contracting-out moratoriums for individual workers, or groups of workers, that elect to work remotely.

- Introduce innovative, and flexible scheduling provisions, where appropriate. These measures could improve work-life balance, especially for new and younger workers, including compressed work weeks and those that enable older workers to gradually exit the workplace (while providing job security for younger members). However, the union must also ensure that these provisions do not contribute to job precarity, lead to a decline in work hours or undermine the creation of stable, full-time jobs.

- Promote greater proportional representation of members in the bargaining process, including at the bargaining table. The union is well served by its participatory and democratic practices in bargaining. However, understanding and adequately addressing the diverse needs of members often requires active and direct engagement among equity-deserving and (often) marginalized groups. Bringing a representative set of voices into the bargaining process can ensure collective bargaining outcomes are more responsive to members.

- Emphasize, at the bargaining table, the connection between strong collective agreements and stable workforces. Contracts that include competitive wages and benefits, more work-life balance, options for working from home, stable scheduling and hours of work, and a pathway to full-time jobs are part of the solution to the problem of worker recruitment and retention.

- Negotiate mandatory apprenticeships. The union can support and encourage skilled trades attraction and retention by negotiating employer commitments to hiring new apprentices, wherever possible.

Job Security and Precarious Work

In the face of new technologies that make it easier or create an incentive to contract-out work, it is essential that our union continue to strengthen job security language in collective agreements. Employers seeking to increase productivity are using new technologies to outsource work to third parties, casualize work, and increase flexibility. These changes are skirting established collective agreement language and laws that are slow to respond to current economic challenges.

We need new members to have the opportunity to see themselves as a Unifor member as soon as they start.

Kitchener-Waterloo, April 4

The increase in precarity through the use of digital platforms and the misclassification of contractors to provide workers to employers for single jobs creates an incentive for employers to casualize labour. The result can be a fractured workforce and reduced union coverage, especially if collective agreement “scope clauses” fail to cover part-time and casual employees or other non-standard groups of workers.

Collective agreement language that supports work ownership, that prevents or discourages contracting-out, and that facilitates the building of sector-wide and/or multi-location pattern bargaining can counteract some of this increased precarious work. Expanding collective agreements to cover casual and misclassified workers will stop the downward pressure on wages and build collective power during bargaining.

The union movement will suffer when members lack hope. We have to inspire workers to be hopeful, so they believe in the power they hold in their hands. That’s how we win.

Halton, April 24

In the face of demographic changes, and as was conveyed by Unifor members during the cross-country Regional Strategy Sessions, the lack of knowledge transfer from one generation of workers to another can also lead to contracting-out of work or deterioration of work standards. If senior members are given the opportunity to train new workers on the job it is more likely that jobs will not be lost to contracting-out. Employers should be forced to provide overlap between generational shifts in the workplace.

The introduction of new technologies and new investments means work done by specific classifications can shift during a workers’ working life. As such, the definition of work for classifications in Unifor’s collective agreements must keep-up with the changing skills required to perform the work. Compensation for these classifications must keep-up with the skills necessary to perform the work covered by the classification.

Bargaining Priorities for Job Security and Precarious Work

To effectively combat the relentless pressure toward precarious, casualized or contracted-out work, and reinforce the rights of collective bargaining across new classifications of workers, we must focus on the following bargaining priorities:

Unifor will:

- Ensure regular assessment and updated classification skills and job duties. The union will seek to ensure a clear identification of classification skills in bargaining surveys to ensure any classification definitions are updated to properly outline the skill-level needed to perform the task. Such assessments must ensure that existing scopes of practice for skilled trades remain intact.

- Bargain work ownership provisions intended to prevent outsourcing or third-party contracting. The union will consider bargaining language that explicitly limits the ability of employers to eliminate jobs during periods of transition or restructuring. This approach will also include proposals to significantly increase costs on employers who choose to outsource work that can be done in-house by bargaining unit members.

- Negotiate succession planning, and inter-generational training. The union will seek to negotiate contract provisions that facilitate intra-classification, inter-generational training for new workers.

- Encourage the creation of full-time, permanent jobs. Unifor will seek to negotiate clear and unambiguous restrictions on the use of part-time or temporary workers, as well as automatic full-time job postings (with full benefits and entitlements) whenever workers are misused to perform full-time bargaining unit work.

- Negotiate equal pay for equal work provisions. The union will seek to negotiate contract language, wherever possible, that ensures workers who are engaged in similar work at full-time, permanent jobs and with the same skills, responsibilities, and working conditions, are paid the same wage, regardless of employment status (such as part-time, temporary, seasonal or contract).

- Skilled trade wage differentials. The union will continue to negotiate wage premiums and other pay differentials for certified skilled trades, in recognition of specialized skills.

- Negotiate broad and inclusive scope clauses. The union will seek to amend scope clauses to include temporary, contract, on-call, and temporary migrant workers.

- Bargain work sharing arrangements, where possible, to avoid layoffs in workplaces. In the event of economic downturns, slowdowns, the union shall consider an application for a Work-Sharing agreement, through the federal government, as an alternative to layoffs and to lessen the financial impact on members in the workplace.

Union Building

Effective bargaining starts with building a strong union, both active in the workplace and tuned in to members’ issues. The daily work accomplished by elected officers, local stewards and committee members is the cornerstone of our movement. This work has evolved over the years, and as the pace of transformation accelerates, new challenges require innovative solutions and the resources to make them a reality.

The COVID-19 pandemic upended many core union activities and transformed interactions with members. For some, it compounded challenges that were already playing out in the workplace. For others, it highlighted new possibilities and effective means to engage with more members, especially some who were at times tuned out of union discussions altogether.

Education remains key to strong union representation and successful bargaining. Members realize that to get the results they want at the bargaining table, they need to grasp how the union works and gain a deeper awareness of the worker movement, its fights andvictoriesas well as losses, to understand where they stand in a fast-changing economy. From basic training to coaching and sharing of tactical and strategic experiences, competency builds worker power.

Accessibility is another fundamental ingredient that needs to be strengthened. At its core, it starts with boots on the ground, stewards involved in the workplace, engaging with members on hot-button issues. Such work requires dedication, but more importantly, sufficient time and resources. Whereas workplace and membership issues have become more complex, union leave provisions must reflect these growing needs and preserve the mental health of those responsible for these essential tasks.

Being accessible is about finding new ways to communicate and making good use of technology. Never in history has there been more ways to connect with one another, yet for some, reaching out and getting the attention of members remains a daunting task. It also means leveraging our membership diversity by revisiting new employee orientation practices and nurturing the presence of all voices in union engagement spaces. Again, those elements are key to sustaining power and influence at the bargaining table.

Laying the groundwork for a successful bargaining round requires a lot of preparation. Correctly assessing the bargaining context is critical and can be achieved with better sharing of information between Unifor locals that operate in the same sector as well as through exploring the creation of new strategic bargaining forums. Financial considerations are also key. They can severely hamper the members’ resolve to fight, especially in uncertain economic times. Addressed early in the process through strike fund measures, they provide confidence and send a strong signal to the employer.

Bargaining Priorities for Union Building

Members participating in the cross-country Regional Strategy Sessions made one message abundantly clear: the basics matter. The need for collective agreement language that facilitates more opportunities for members to do effective union work is still a front and centre issue.

In parallel, wide-ranging education and training options, active union presence in the workplace, updated communications and technological supports, greater recognition of membership diversity, better internal coordination and steadfast early-set preparations were also seen as key drivers for success at the bargaining table.

Unifor will:

- Negotiate for more workplace representatives. Work accomplished by elected officers, workplace stewards and committeepersons underpin all our collective gains. Increased member representation is needed to tackle workplace matters, whether they are related to health and safety, equity, women, workplace benefits, skilled trades, or other bargaining-related issues.

- Negotiate increased paid union leave time for representatives, including during scheduled work hours. Workplace and membership issues have not only increased, but also become more complex. Members tasked with solving these issues require additional time and resources to be effective and maintain work-union-life balance.

- Negotiate employer-funded Paid Education Leave (PEL). Informed, competent, and confident members are a crucial component of successful bargaining. If PEL funding already exists, local committees should aim to increase contributions, and explore other measures to make educational opportunities more accessible for members.

- Negotiate Unifor’s 40-hour Women Skilled Trades & Technology Awareness Program. Increasing diversity, and especially the participation of women in the Skilled Trades, is a priority for the union. Negotiating employer contributions, and member access, to the 40-hour ‘Women in Trades’ program provides useful information and a pathway for more women into the trades.

- Bargain employer contributions to the Social Justice Fund (SJF). The union’s SJF offers solidarity and support to workers and communities at home and abroad for development, emergency relief and the fight for socioeconomic justice. Where SJF funding already exists, local committees should aim to increase SJF contributions.

- Negotiate language on union-led new member orientation in the workplace. Employers must let unions engage and provide paid orientation time for new employees to meet with elected workplace representatives and learn about the union upon hiring. This first contact is crucial in establishing union relevance and building trust.

- Negotiate language facilitating union access to updated membership lists. Employers must provide unions with easy and timely access to updated information about their members, at regular intervals and over the life of the collective agreement.