Sector Facts and Figures

| Sector Facts and Figures | |

| OUTPUT | |

Sector GDP Share of Canadian GDP | $1.1 billion 0.1% |

| TRADE | |

| Exports | $0.5 billion |

| Imports | $2.2 billion |

| Export reliance | 10.9% |

| U.S. dependence | 7.0% |

| Foreign Trade Balance | -$1.7 billion |

| EMPLOYMENT | |

Total Employment 10-year change | 10,200 +56.8% |

| Average hourly wage | $45.80/hr |

10-year real wage change | +26.7% |

| Average Work Hours/Week | 37.1 |

| ENVIRONMENT | |

Greenhouse Gas Emissions (2022) 10-year change Share of Canadian industry total | 44kt +110% 0.01% |

| LABOUR | |

| Union Coverage Rate | 52.3% |

| Unifor Members in the Industry | 1,200 |

| Share of Total Unifor Membership | 0.4%

|

| Number of Unifor Bargaining Units | 4 |

Unifor in the Shipbuilding Industry

Unifor represents roughly 1,200 workers in shipbuilding, representing 0.4% of all Unifor membership. The majority of these members work in Nova Scotia, at Irving’s Halifax Shipyard. Unifor shipbuilding members also work for Marine Fabricators and Shelburne Ship Repair, preparing steel for construction at Halifax Shipyard and performing vital maintenance and repair on large vessels.

Unifor members in the shipbuilding industry work primarily in a variety of skilled trades, including electricians, millwrights, machinists, crane operators, welders, and pipefitters.

| Select Unifor Employers | Approx. # Members |

| Irving Co. | 1,025 |

| Marine Fabricators | 60 |

| Shelburne Ship Repair | 50 |

Current Conditions

Although the shipbuilding industry is relatively small compared to some of the other sectors represented by Unifor – with the industry contributing $1.1 billion or 0.1% of Canada’s total economic output in 2024 – it occupies a particularly strategic position within the economy and is a vital part of coastal communities. A robust shipbuilding industry is crucial for maintaining the independence of Canada’s national defense and security, while providing thousands of quality jobs and promoting advanced innovation in marine technologies.

The federal government recognized the critical importance of shipbuilding with the 2010 launch of the National Shipbuilding Strategy (NSS), a long-term plan aimed at revitalizing what was then a declining industry. Under the strategy, three shipyards have been selected for the construction of large vessels, including Irving shipyard in Halifax where advanced River-class destroyers and Arctic/offshore patrol ships will be built by Unifor members. The umbrella agreement also encompasses Vancouver Shipyards and was expanded in 2023 to include Chantier Davie Canada in Lévis, Quebec.

The strategy has also contributed to the development of a highly skilled workforce. Irving Shipbuilding has hired hundreds of skilled trade apprentices over the past decade, with more than half achieving Red Seal certification. Innovative training initiatives, including the Pathways to Shipbuilding Program, aim to increase job opportunities for Indigenous and racialized workers and to train more women in the skilled trades. As a result, Unifor MWF Local 1 now represents the largest number of trades apprentices in Atlantic Canada.

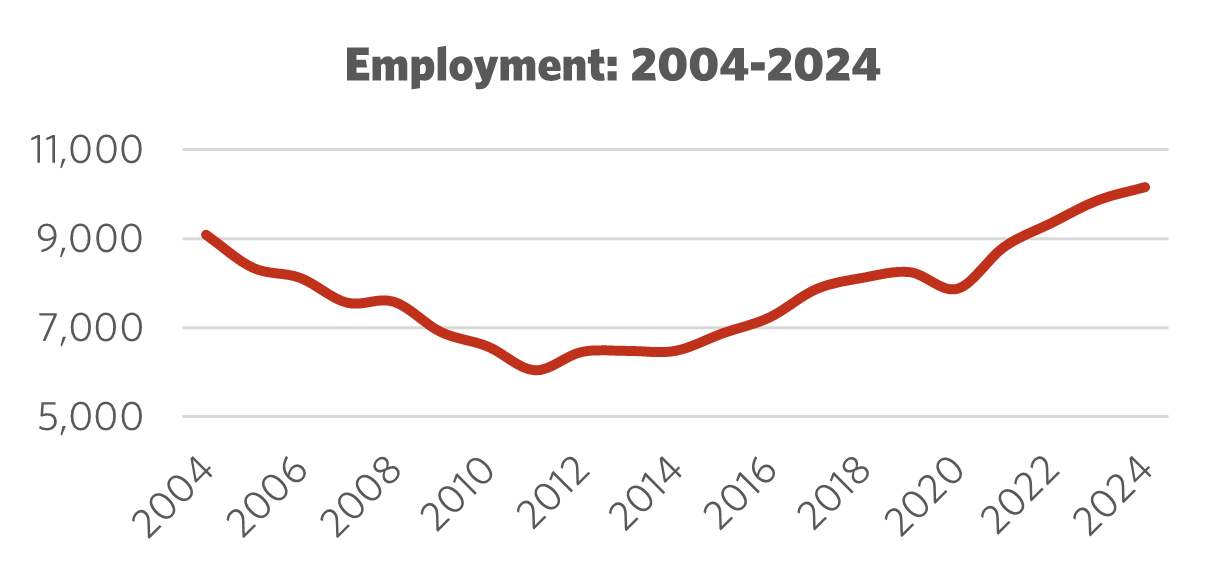

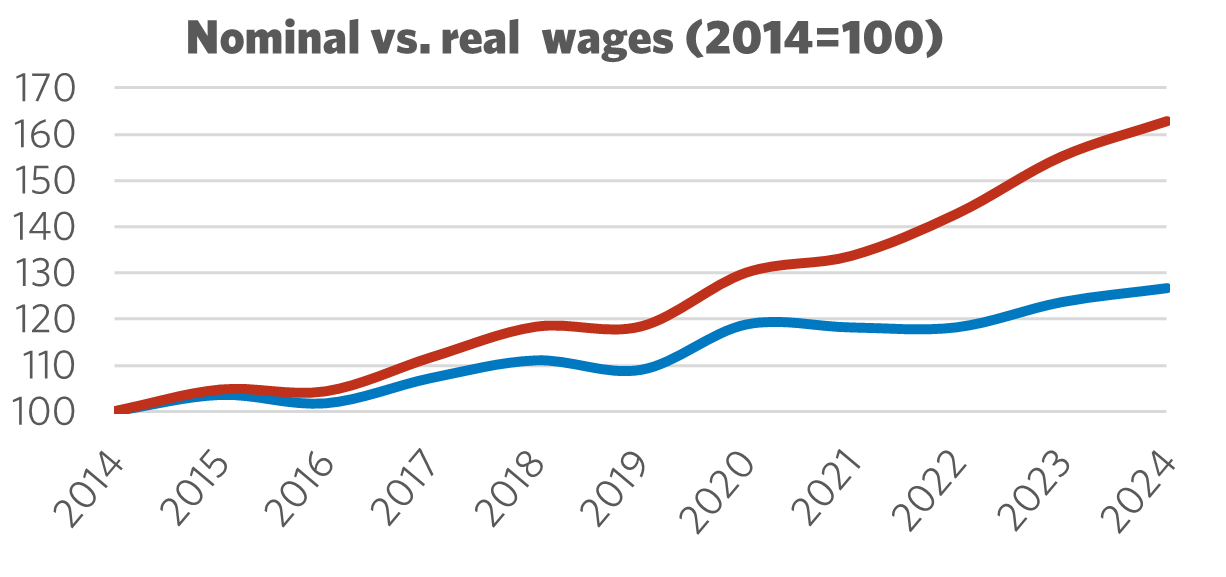

The National Shipbuilding Strategy has led to a spectacular turnaround for the industry’s employment and wage levels. Total employment has increased by nearly 57% since 2014, rising to above 10,000 workers for the sector as a whole with nearly 2,000 jobs added in the past three years alone. Wages have recorded similarly impressive growth, thanks to strong Unifor collective bargaining, with inflation-adjusted gains sitting at 24% over the past decade. This is in stark contrast to a number of industries where higher inflation during the post-pandemic period has eroded workers’ purchasing power.

Figure 1: Employment 2004 – 2024

Figure 2: Nominal vs. Real Wages (2014 = 100)

Moving Forward: Developing the Shipbuilding Industry

Despite the success of the National Shipbuilding Strategy, Canada’s shipbuilding industry faces significant challenges to future development and expansion. While the industry’s export reliance sits at just under 11%, with 7% of total manufacturing going to the U.S., the Trump Administration’s efforts to revive U.S. shipbuilding capacity and reduce dependence on Chinese-built vessels may ultimately place Canada’s industry in the crosshairs of an expanding trade war. The federal government must prioritize keeping tariffs off of Canadian ships and components while increasing domestic procurement of Canadian-built ships.

Another major issue has been continuing skepticism surrounding complex and costly domestic projects like the Canadian Surface Combatant (CSC) program, which will construct 15 River-class destroyers at Halifax shipyard. Critics of the program have argued that off-the-shelf vessels from overseas would be significantly cheaper and faster to deliver, but this argument overlooks the long-term economic and strategic benefits of maintaining a robust domestic shipbuilding capacity. It also ignores the fact that the shipbuilding industry is particularly vulnerable to the effects of inflation-driven cost increases and delivery delays, which are common in highly complex procurement but often unfairly blamed on domestic production rather than broader economic factors.

Abandoning the National Shipbuilding Strategy would mean the loss of thousands of good unionized jobs while increasing Canada’s reliance on the ability of foreign suppliers to deliver vessels on time and on budget. This would present an unacceptable risk to national security and drastically weaken Canada’s domestic manufacturing capacity precisely at a time when government should be investing in shoring up heavy industries. Government must continue supporting skilled workforce development in the industry, including improving access for underrepresented groups through programs like Unifor’s Pathways to Shipbuilding, while expanding other forms of shipbuilding procurement to create good jobs, meet Canada’s economic and security needs, and provide lasting benefits to coastal communities.

Sector Development Recommendations

- The federal government must signal a renewed commitment to the National Shipbuilding Strategy (NSS), while ensuring that Canada’s shipbuilding industry avoids future U.S. tariffs as the Trump Administration moves to revive U.S. shipbuilding capacity.

- Domestic procurement of Canadian ships must be bolstered to support thousands of unionized jobs and reduce Canada’s reliance on foreign suppliers, which would otherwise threaten national security and weaken domestic manufacturing capacity at a critical time.

- Continued government support is essential for workforce development—including improving access for underrepresented groups—and expanding shipbuilding procurement to fulfill Canada’s economic and security needs while training more skilled workers.