Sector Facts and Figures

| Sector Facts and Figures | |

| OUTPUT | |

Sector GDP Share of Canadian GDP | $38.3 billion 1.9% |

| TRADE | |

| Exports | $99.6 billion |

| Imports | $64.3 billion |

| Foreign Trade Balance | +$35.3 billion |

| EMPLOYMENT | |

Total Employment 10-year change | 230,662 +7.8% |

| Percentage of part-time workers | 2.5% |

| Average hourly wage | $52.40/hr |

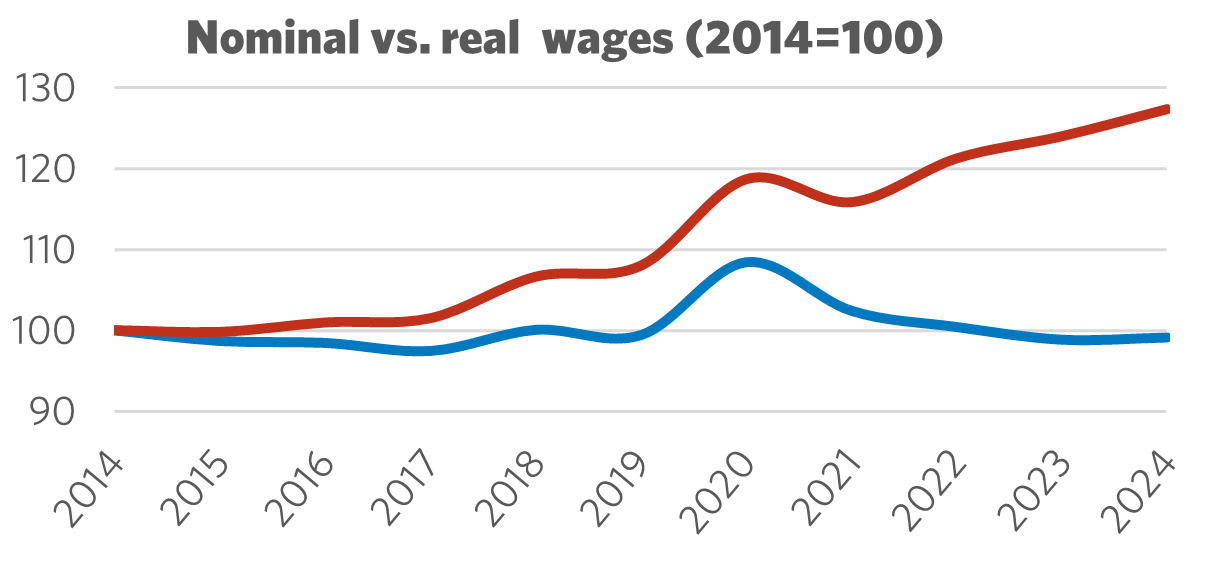

10-year real wage change | -0.9% |

| Average Work Hours/Week | 38.1 |

| ENVIRONMENT | |

Greenhouse Gas Emissions (2022) 10-year change Share of Canadian industry total | 28,520kt -4.2% 4.5% |

| LABOUR | |

| Union Coverage Rate | 23.9% |

| Unifor Members in the Industry | 9,000 |

| Share of Total Unifor Membership | 2.8%

|

| Number of Unifor Bargaining Units | 64 |

Unifor in the Mines, Metals and Minerals Industry

Unifor's 9,000 workers represented in the industry account for approximately one-fifth of Unifor's natural resources membership and just under 3% of its overall membership. The majority of Unifor's members in the mines, metals and minerals work in Quebec and Ontario, with both provinces accounting for a combined 59% of the industry’s membership. British Columbia follows with 18% of the industry's Unifor membership, while Saskatchewan covers around 15%. The remaining 8% of members are located in Alberta, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. Union coverage in the industry is relatively strong for the private sector, standing at close to 24%. Around half of all Unifor members in the industry work for the five largest employers, with Rio Tinto leading the way at just over 2,400 members. The sector encompasses a diverse range of operations, including non-petroleum hard-rock mining, aluminum and non-ferrous smelting, as well as mineral extraction, particularly in potash and salt.

| Select Unifor Employers | Approx. # Members |

| Rio Tinto | 2,400 |

| Mosaic | 850 |

| Glencore | 800 |

| Gibraltar Mines | 500 |

| Nutrien | 450 |

Current Conditions

The mines, metals and minerals industry remains a crucial engine of economic growth for Canada, contributing over $38 billion in gross domestic product (GDP) in 2024, which amounted to nearly 2% of Canada’s economic output. During the same year, the industry generated nearly $100 billion in export value and maintained a trade surplus of $35 billion. Despite relatively sustained growth, the industry managed to decrease its greenhouse gas emissions from 2012 to 2022 by over 4% due to reliance on lower carbon energy sources and widespread electrification of mining operations.

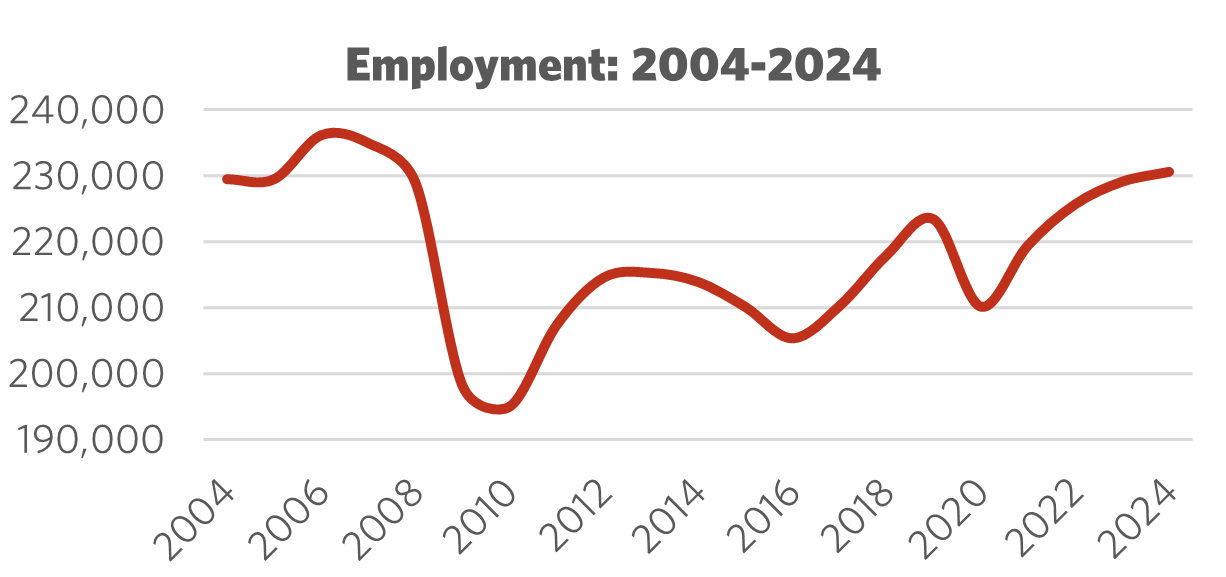

Workers in the mines, metals and minerals industry have weathered significant volatility over the past two decades. After enjoying over a decade of surging commodity prices starting in 1996, the sector faced a significant downturn in 2006-7 which coincided with plummeting prices and the onset of the 2008-9 financial crisis. Employment in the industry dropped by 17% between 2006 and 2010, though a brief recovery helped regain about half of those lost jobs by 2012. However, continued declines and stagnation in commodity prices led to further layoffs, until a sustained recovery began in 2016 which was only briefly interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are now signs that the mines, metals and minerals industry may be entering a new phase of sustained growth, with industry employment increasing by 10% since 2020 to 230,600 in 2024, surpassing 2004 levels. This is being driven in part by the return of post-pandemic demand, as well as structural shifts towards renewable technologies and other commodity-intensive forms of growth. The industry is poised to play a central role in supplying the raw materials needed for this new generation of zero-emission technologies that are expected to revolutionize energy production and transportation. Trade tensions with the United States and the Trump administration’s imposition of tariffs on Canadian aluminum and steel may dent this upwards trajectory, although long-term prospects remain strong given global demand and Canada’s vast mineral wealth.

Figure 1: Employment 2004 – 2024

Figure 2: Nominal vs. Real Wages (2014 = 100)

Moving Forward: Developing the Mines, Metals and Minerals Industry

While development of the mines, metals and minerals industry is often touted as being key to Canada’s future economic success, the industry faces a number of critical challenges at this juncture, including overcoming current trade tensions with the United States. The decision by the Trump Administration to impose damaging tariffs on Canada’s steel and aluminum exports to the U.S. has seriously damaged the reliability of a key trade relationship for the industry, which supplies nearly two-thirds of U.S. aluminum imports and a quarter of its steel imports. Although all indications suggest that the U.S. will be unable to fully replace Canadian sources of steel, aluminum and other key metals and minerals, development of the industry can no longer assume shared economic interests with the U.S. It will be vital to diversify Canada’s exports while ensuring that future manufacturing capacity and infrastructure development launched as part of any nation-building initiative are powered by Canadian metals and minerals. On this front, fostering strong, respectful partnerships with Indigenous communities and taking seriously the duty consult within the framework of Indigenous treaty rights will be paramount as Canada moves to expand its mining base.

After a slow start to implementing the vision laid out by the federal Critical Minerals Strategy, governments at all levels have urgently signalled the need to develop Canada’s mineral wealth in the face of U.S. tariffs. In this context, legislation such as Ontario’s Bill 5 and the federal government’s Bill C-5 could pose a significant threat to both Indigenous and labour rights, as governments use the excuse of fast-tracking mining projects to override established protections. Such measures also highlight the continued challenges of ensuring that development of the mines, metals and minerals industry also reduces its environmental footprint, with the industry having successfully lowered emissions by more than 4% since 2012. Government must continue to support efforts to decarbonize operations while ensuring such initiatives are not used by employers to reduce jobs through greater use of automation and the deployment of artificial intelligence (AI). On this last point, confronting the threat of AI to workers’ privacy and job security through increased surveillance and workforce reductions will require both legislative intervention and concerted social dialogue between labour and employers.

Sector Development Recommendations

- Immediately negotiate an end to U.S. tariffs on Canadian aluminum and steel, which are significantly impacting two of the most critical exports to the U.S. while threatening Canada’s primary and secondary metal manufacturing base.

- Canada must diversify its trading partnerships and ensure that future manufacturing and infrastructure developments rely on Canadian metals and minerals, rather than assuming continued access to U.S. markets.

- Building strong, respectful partnerships with Indigenous communities is essential, particularly regarding consultation and treaty rights. Legislation passed under the guise of developing the industry – such as Ontario’s Bill 5 – could threaten both Indigenous and labour rights by fast-tracking mining projects at the expense of established protections.

- Legislation and social dialogue between labour and employers are needed to address impacts on workers’ privacy and job security as the industry continues to decarbonize and expand its use of AI and automation.