Share

I am not a member of a political party. I recognize the importance of elections, participate in election campaigns (including canvassing and raising money for good candidates), and engage heavily in election-related debates (like the detailed critique of the Harper government’s economic record I co-authored, with Jordan Brennan, for Unifor). But I am skeptical of the motivations and opportunism of electoral parties, perpetually disappointed by their cynical and often unprincipled actions, and unwilling to compromise what I think are clear and important progressive ideas for the sake of a party's “brand.” I have concluded that the most effective contribution I can personally make to social change is to focus on the ongoing intellectual and ideological contest over what sort of economy and society is desirable and attainable. That ongoing “battle of ideas,” not the quadrennial battle of party logos, is what ultimately determines our trajectory as a society.

To some extent, election campaigns do become “battles of ideas”, as the various parties explain and advocate their preferred platforms. But more commonly they actually stay away from debating the merits of particular issues: instead, campaigns tend to be dominated by the efforts of competing parties to pitch their platforms at a winning slice of the electorate, taking the starting opinions of the voters as more-or-less given. In an era of message-testing and focus-group-driven politics, the goal is not to change the minds of voters, pushing them in a certain direction, so much as to make sure your platform appeals to enough of them to get elected. That is quite a different vision of politics. The goal is to win the election, whatever the views of Canadians, not to change those views (apart, of course, from changing their views about the desirability of a particular party or leader).

This creates an unappealing quandary for progressives, who are running for office precisely because they want to change society. As Tom Walkom put it, for a left-wing party, what is the point of winning an election, if you have to move substantially to the right in order to appeal to enough voters to win? If you don’t campaign on progressive ideas, you can hardly implement progressive policies even if you do win. But at the same time, what’s the point of being a political party, if you never have a chance of winning? That is a genuine quandary (and one that requires a more complex answer than just saying that the NDP should have run on a more progressive platform!).

Particularly in our first-past-the-post electoral system, but even under better electoral models, the logic of electoralism imposes a race to the middle on the part of all political parties. Tom Flanagan describes this imperative as the competition to win over the “median voter” (citing Anthony Downs’ work); in economic theory, a similar thinking informs Kenneth Arrow’s impossibility theorem. In this light, the repeated centrist lurches by left-wing parties that have caused such disappointment for progressives around the world (including the NDP’s surprising platform in this election) shouldn’t be surprising.

If we want to shift politics to the left, therefore, we need to change the views of the “median voter” (or more generally the “common sense” economic wisdom of Canadians generally), so that political parties see it in their electoral interests to enunciate more progressive views. That is precisely the goal of progressive social movements, trade unions, and research institutes – groups that engage in the battle of ideas all the time, not just in elections. (For example, Unifor described a model of ongoing political and social activism quite similar to this view in its 2014 paper “Politics for Workers.”)

Did the median voter’s views on economic issues change during the 2015 federal campaign? Or did the parties just carve up that terrain differently? Most post-mortems have focused on the strategic positioning of the various parties, rather than on changes in the actual opinions and values held by Canadians. The NDP’s effort to capture a broader swath of centrist opinion with its cautious economic platform seems to have backfired. The Liberals effectively captured the mantle of “change,” gathering the bulk of anti-Conservative opinion around them. The Harper Conservatives’ divisive policies over four years obviously narrowed their appeal (although they retain a strong base of support that progressives would be unwise to discount). In these commentaries, the shifting electoral landscape mostly reflects the relative success of the positioning and communications efforts of the competing parties, more than any shift in the actual ideas held by Canadians. (One exception to this “slice and dice” mode of analysis is Ken Boessenkool and Sean Speer’s article which examined the change in Canadians’ attitudes toward deficits.)

I will leave it to political pundits to second-guess the strategic positioning of the various parties. I am ultimately more interested in how the election reflected shifts in Canadians’ underlying attitudes toward key economic issues. Those shifts may have come about because of the election campaign itself (if a party put forward a new idea in an effective and convincing manner). More likely, they reflected ideological seeds planted long before the writ was dropped, through the ongoing debate, research, and advocacy campaigns that affect Canadians’ deeper attitudes and opinions.

Did the “common sense” economic attitudes of Canadians become more progressive, and that’s why Conservatives lost and Liberals were rewarded for their promises of “change”? Or were the Liberals simply more effective at slicing-and-dicing an electorate whose outlook on economic issues is not really much different than it was when Harper Conservatives were being elected? The answer to this dichotomy will affect whether or not real change is likely to unfold in the wake of this election. I think the answer is probably: “a bit of both.”

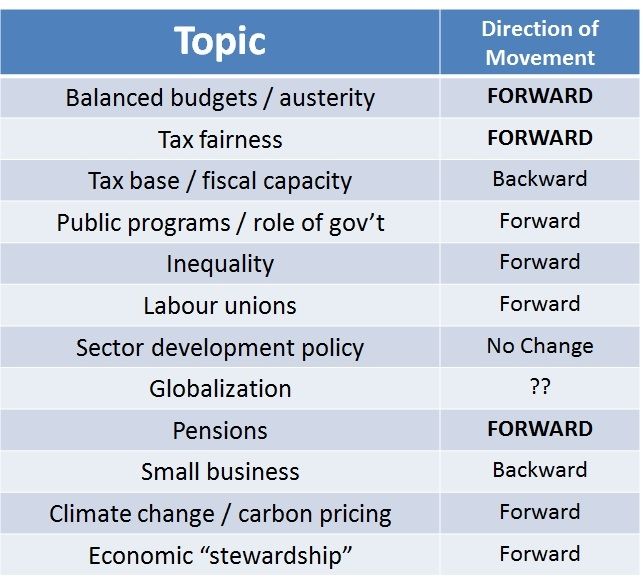

The table below summarizes how I think the election reflected, and perhaps contributed to, changing views on economic issues. I indicate whether public views on those various issues seem to have moved forward (that means more progressive, in my world view), backward, or unchanged. A significant movement is indicated in bold caps; a weaker movement in plain font. These assessments are based solely on my observation; more rigorous assessments (such as with formal polling and opinion research) would be required to confirm and describe these shifts in more detail.

Deficits and austerity (FORWARD): The election marked a significant shift in “common sense” wisdom regarding deficits. The Conservatives’ phony achievement in balancing the books (recording a small “surprise” surplus mid-campaign) didn’t generate the electoral dividends they expected. The Liberal plan to run small deficits (amounting to just 0.5% of GDP for three years) became a potent symbol of their willingness to use the levers of government to try to stimulate economic progress. That symbolism was ultimately more important than the actual modest stimulus that would be generated by running those deficits. The NDP’s effort to appear more economically “acceptable” by promising to balance the budget (despite weak macroeconomic conditions) backfired. Simple-minded claims that the government must balance a budget just like households do (both parts of that claim are ridiculous: hasn’t anyone noticed household debt levels in Canada recently??) no longer rule the day in public fiscal debates. Of course, the progress is incremental: the Liberal deficits are small and temporary, and just running a deficit by itself doesn’t really improve things (it depends on what discretionary actions caused the deficit). But the deficit- and debt-phobia which has dominated fiscal discourse in Canada since the early 1990s has definitely been damaged. (The Ontario and Alberta elections also attest to this incremental but important shift in public attitudes.)

Tax fairness (FORWARD): Another topic on which Canadian attitudes seem to have progressed is on the fairness of the tax system. The Liberals proposed a series of changes in tax and transfer measures which will engineer a modest progressive twist in the incidence of net federal taxes. Both the Liberals and the NDP pledged to roll back two very regressive Conservative measures: doubling the TFSA (a gift to the 1%) and income splitting (a bone for Harper’s social conservative base). A year ago, we all feared that by locking these measures in before the election (and hence committing most of future surpluses before the election was even called), the Tories might be able to buy their way to another election victory. Thankfully, Canadians were not so easily lured by the aura of their own money, and strong critiques of both those measures were forthcoming from many sources (David MacDonald’s work for the CCPA on the distributional impacts of income-splitting was especially important). The Liberals proposed incremental measures to shift the net burden of personal income taxes to higher-income households, creating a new tax rate for the top 1% of households (and raising their marginal tax rates by a substantial 4 percentage points, more than that when add-on provincial taxes are considered), cutting the “middle” rate by 1.5 points, and restructuring the entire child benefit system in a progressive manner (replacing Conservative baby bonus cheques with a more focused and progressive benefit). The NDP endorsed the Conservative baby bonus system (disappointing social policy advocates who have been working for a generation to build a progressive targeted system through the CCTB) and strongly opposed any increase in personal income taxes, even for high-income individuals (Thomas Mulcair railed passionately against higher taxes for rich people as “confiscatory”). The NDP’s proposal to raise corporate taxes was progressive, since corporate wealth is owned so disproportionately by high-income Canadians – although its offsetting proposal to cut small business taxes was regressive, for exactly the same reason. The broad theme that the tax system has become too favourable to the wealthy, and should be reformed in a progressive way, resonated well for the Liberals, and this is a good sign.

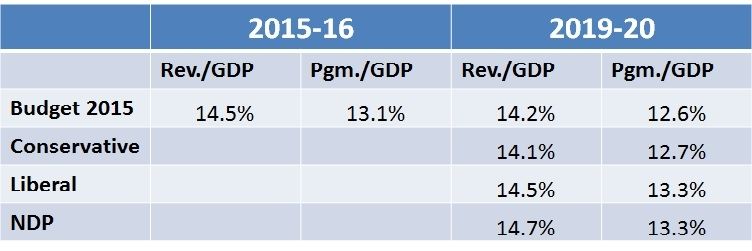

Fiscal capacity (backward): While Canadians were receptive to the argument that the wealthy should pay more taxes (not less, as under the Conservative plan), there was no real effort made by any of the parties to reinforce the general fiscal base of the federal government. Much of the revenue from new taxes proposed by the Liberals (high-income tax bracket) and the NDP (two-point hike in the corporate tax rate) was largely used up to pay for tax reductions targeted at other constituencies (including the “middle” tax rate reduction for the Liberals, and the small business tax cut for the NDP). So while both those parties advocated modest shifts in the incidence of the tax system (toward high-income earners for the Liberals, and toward corporations for the NDP), neither was really willing to repair the general erosion of the tax base which Harper engineered. As shown in the second table, for the Liberals federal revenues would be equal (as a share of GDP) in the fourth year of their plan, as they are today (after a decade of Harper tax cuts). For the NDP, they would grow by 0.2% of GDP. For the most part, therefore, the historic decline in federal revenues as a share of GDP engineered by the Harper government (the revenue share fell from 16% in 2006 to 14.3% last year) would be ratified and sustained (although at least the revenue share would stop falling, while under the Conservative platform it would have continued its decline). I would argue that this reduction in the tax base is in fact the most lasting (and destructive) “legacy” of Harper’s decade in power; it embodies the long-term success of his “starve the beast” approach to fiscal policy, and if anything this election reinforced the staying power of his legacy. The fact that neither opposition party was really willing to challenge that legacy (in the face of daunting political obstacles) shows how much work progressives have to do, to rebuild “common sense” acceptance of strong taxes (paid by everyone, not just the rich and corporations) as a precondition for high-quality public programs and services. The silver lining is that both the Liberals and the NDP were prepared to stop the downward slide in federal revenues.

Source: Author's calculations from party platforms and 2015 Budget Plan. Includes EI revenues and spending (accounted separately in the NDP platform).

Public programs (forward): Both the Liberals and the NDP proposed a range of new public programs and services (the NDP platform was more ambitious and specific on this score, but the Liberal platform had somewhat more money in it), and the general idea that government should provide those things as a core function of its mandate was strengthened through this campaign. Under the Liberal platform, program spending would rise slightly as a share of GDP; under the NDP platform it would stabilize at current levels (compared to the decline anticipated in Budget 2015, and ratified in the Conservative platform – see table). In contrast, the Conservative touchstone that Canadians should get to “keep their money” and spend it on whatever they think is most important, was less effective than in the past. (However, we should acknowledge that that “anti-big-government” ideology is still strong among one-third of society.) Progressives need to ramp up their arguments about the many benefits of public provision, if we are going to make more progress on this front in the future.

Inequality (forward): There is much evidence (from polling and other sources) that Canadians have become concerned with growing income inequality in recent years, and I believe this sensitivity contributed to the way the campaign unfolded. Conservatives were vulnerable to criticisms that their tax cuts would disproportionately benefit high-income earners, and that vulnerability is testimony to groundwork laid by inequality researchers and activists over the last decade. The fact that the Liberals would actually campaign (and successfully, too) on a significant tax increase imposed on “the 1 percent” attests to the lasting influence of the Occupy movement – and all the researchers and activists who supported it.

Labour unions (forward): A multi-dimensional attack on the freedom, social legitimacy, and fiscal base of the labour movement was a key theme of the Harper government’s reign – especially under their majority mandate. This attack on organized labour ultimately failed: Harper is gone, and the labour movement is still here. Damaged, on defence, but still here, and still powerful. The Liberals pledged explicitly to unwind some of the most offensive Conservative measures, including restoring free bargaining with federal public servants, and cancelling private member bills C-377 and C-525. Undoing the latter (and restoring card-based certification in the federal sector) will put the new government in conflict with important business voices (like WestJet) who would prefer that measure was eliminated. Unions played an important role in helping to damage the Conservative brand in the lead-up to the campaign, and during it. Perhaps even more important than Liberal legislative promises, is the restoration of the general idea that unions can be a positive, legitimate partner in social dialogue and policy-making. Harper’s defeat on this score follows the crushing defeat of Tim Hudak’s virulently anti-union platform in Ontario in 2014. I hope these twin outcomes will convince Conservatives across Canada that it doesn’t pay to attack labour rights (though I am not holding my breath). At any rate, the formidable efforts of unions to resist the Conservatives’ anti-labour vision have made a big difference.

Sector development policy (no change): At the level of ideology, Conservatives have enunciated a broadly laissez faire vision which eschews “picking winners,” and accepted (even celebrated) Canada’s growing resource-dependence. But at the level of economic and political practice, they were surprisingly “hands-on.” Their support (driven by minority politics as well as economic desperation) for the expensive rescue of GM and Chrysler in 2009 is the best example of that inconsistency, but there are many others – including several carefully-targeted campaign promises for auto, manufacturing, ICT, and other strategic sectors unveiled during the campaign. The Liberal platform, in contrast, was surprisingly silent on sector-focused initiatives. The new government will face pressure to step up to the plate for auto, aerospace, innovation, and other priorities. Their breakthroughs in Ontario and Quebec will reinforce the political pressure for intervention to support key central Canadian industries. On the other hand, the views of the government are unclear in this area, and advocates for active sector strategies will need to push hard. The NDP enunciated a more explicit and progressive approach to key sectors, although with modest funding commitments.

Globalization (??): This set of issues proved to be especially interesting and surprising during the campaign. The Conservatives desperately hoped for a blockbuster breakthrough at the TPP talks to reinforce their “reputation” as capable economic managers. (Of course, CETA, the last “blockbuster” deal brought home by the Conservatives, still amounts to a big fat zero, two years after Harper’s ostentatious signing ceremony in Brussels.) They didn’t get it from the Hawaii round in July, just as they were preparing to drop the writ. Then, subsequent debate and leaks brought attention to surprising concessions which were being demanded of Canada – including far-reaching concessions on auto content rules (negotiated without Canada’s knowledge or participation) that forced key industry voices (led by the Automotive Parts Manufacturers Association) to speak against what was happening. By the time a final deal was reached in Atlanta, barely two weeks before the vote, it was no longer a clear vote-winner for the Conservatives. They didn’t even speak much about the TPP in the dying days of the campaign. Unifor’s punchy anti-TPP campaign focused on Conservative incumbents in auto communities; 14 of them went down to defeat, and Unifor’s campaign was definitely a factor. There were many reasons for Canadians to be concerned about the effects of the TPP in several sectors, and the lack of transparency around the agreed text only reinforced public suspicions. The Liberals straddled the “wait and see” fence. Meanwhile, the NDP had spent the last three years cozying up to free trade (including endorsing the Canada-Korea deal, which is already a disaster for Canada, less than a year in), and Mr. Mulcair’s initial comments on the TPP were receptive. But as the NDP’s polling numbers deteriorated, they seized on the TPP as a wedge issue to prove they were more “progressive” than the Liberals, and shifted to a strongly oppositional position. This effort was not very successful, given their transparently electoral motivations and the inconsistency with past positioning. We are now left with a bad deal, signed by Conservatives for political reasons, that the Liberals are very likely to want to ratify (after a requisite period of “consultation” and study). On the other hand, the ratification process in the U.S. will be complicated and uncertain, and there may even be an opportunity for revising some TPP terms. I honestly don’t know whether progressive positions about globalization are stronger or weaker after this election. The TPP process provided alter-globalization arguments and activists with a new opening, new arguments, and some new relevance. On the other hand, the consensus among the powers-that-be around the benefits of the TPP and similar deals is extremely strong (as is the ideological apparatus used to reinforce that “consensus”). Progressives need to think carefully about their strategic focus for continuing to challenge the TPP and other aspects of modern globalization, without sounding like a broken record.

Pensions (FORWARD): The election has opened up huge opportunities for the fight for fair pensions. The Liberals were committed to an “enhancement” of the CPP, restoring the retirement age for OAS/GIS purposes to 65, and cancelling the TFSA expansion. These are all important and positive changes, and in together constitute a frontal blow to the individual-savings model of pension policy. The CPP enhancement will be tricky and contested, and the labour movement and other progressive pension constituencies will need to be fully focused and engaged. All provincial governments will be open to CPP expansion (especially Ontario, where the election has the potential benefit of making the provincial ORPP proposal redundant), but the small business and financial lobbies will pull out all the stops to defeat or limit the expansion.

Small business (backward): The ideological aura surrounding the virtues of the small business community became a little thicker still in this election – even though small business lobbyists will not be happy with the outcome. The NDP led the way with its proposed 2-point cut in the small business tax rate early this year, a promise which was quickly ratified by the Conservatives (not wanting to be outdone) in their 2015 budget. The Liberals caved and promised a matching cut in future years. Arguments from economists (even mainstream economists) and inequality experts that this tax cut was neither fair nor effective were lost in the celebration of small business as the greatest “job-creators” in society (a claim that is barely true in an arithmetic sense, and fundamentally wrong in any meaningful or behavioural sense). And the idea that the best way to stimulate more small business activity is to cut their taxes is badly misplaced (given how marginal small business taxes are to start with). A far better way to help small business is to stimulate domestic demand for goods and services, which is the true constraint facing most small firms (not their taxes). Most outrageous of all was what happened when Justin Trudeau pointed out (completely accurately and justifiably) that favourable tax treatment for small business is commonly mis-used as a legal form of tax evasion by the owners of Canadian-Controlled Private Corporations (CCPCs, the legal entity which many savvy high-income individuals set up to shelter income and avoid taxes). This elicited a bizarre tag-team attack from Conservatives and NDPers alike accusing Mr. Trudeau of “insulting” the hard-working small business owners who are the true engine of growth. This nauseating example of party positioning trumping intellectual integrity affirmed for me the validity of my non-partisan approach to research and policy described above. This whole issue is just begging for further progressive analysis of the problems of small business tax incentives, the problems of an economy dependent on self-employment and very small firms, the challenges of growing bigger firms (instead of subsidizing very small ones), and the link between inequality and small business ownership. This is not to discount the progressive analysis which has been forthcoming on those topics (from folks like Seth Klein, Mike Veall, Hugh Mackenzie, and others), just to make the obvious point that we need a lot more of that research – and we need to communicate it a lot louder – to discourage the pap but flawed arguments that proved so influential during this campaign.

Climate change / carbon pricing (forward): The Conservatives tried again to raise the bogeyman of “job-killing carbon taxes” to attack any proposal for meaningful carbon regulations in Canada. Luckily their strategy did not work this time (like it did when they massacred Stéphane Dion’s green shift). The ongoing “battle of ideas” played a crucial role in this change. From mainstream initiatives (like the EcoFiscal Commission) to more radical research and education work, the ground was clearly laid for Canadians to accept that some kind of carbon pricing is both inevitable and necessary. Of course, the process of implementing the Liberal proposal for a flexible national-but-provincially-based carbon pricing regime, specifying targets and enforcement mechanisms, will be enormously difficult and controversial. But just seeing the discrediting of Harper’s head-in-the-sand approach is an enormous step forward in this realm. Coming just weeks after the ousting of Australia’s similarly retrograde Prime Minister Tony Abbott, this means that both halves of the infamous “Axis of Denial” (which so sabotaged international climate negotiations in recent years) have been relegated to the scrap heap of history. And that’s a victory for the planet, not just for Canadians.

Economic “stewardship” (forward): I think there is one more diffuse but important dimension in which we moved the needle forward this election, in the battle of economic ideas. The assumption that Conservatives naturally know how to best manage the economy has been well-engrained in popular discourse. Like other components of “common sense,” this hegemony is reinforced through careful cultivation by the instruments of ideological power in society: including the media, corporate-funded universities, think tanks, business leaders, and more. The traditional idea is that “the economy” is the realm of hard-headed business-friendly types, while “social issues” are the realm of soft-hearted caring-sharing types. In most elections, “hard” pocketbook issues and perceived material and financial self-interest trump “softer” policy concerns, and Conservatives always try to play this “economic card” energetically. Rightly or wrongly, polls traditionally indicated that most Canadians viewed Conservatives as the best economic managers. Even NDPers would play into this constraining dichotomy by assuming that economic issues are not their strong suit, motivating an ongoing effort to shift the debate to other topics. (Alternatively, they would try to burnish their economic credentials by mimicking many Conservative policies, which is even worse.) A more fundamental challenge could be launched against the traditional assumption that Conservatives best know the economy, by pointing out that for most Canadians, economic well-being and security have stagnated or even deteriorated under their rule. This approach tries to reclaim the definition of “economic performance,” noting that the only indicator of success is whether the human needs of Canadians are being met more successfully, or not. On that score, we made some progress, and by the end of the campaign, polls no longer showed the Conservatives with any consistent advantage on the matter of “economic stewardship.” This success was based on many factors: the ongoing weakness of Canada’s macroeconomic performance (including the advent of an official recession just as the campaign was getting underway, disastrous timing for the Conservatives), the efforts of the opposition parties to construct credible and attractive economic platforms, and the efforts of popular organizations (like Unifor) to challenge the Conservatives’ economic credibility. Of course, progressives need to advance our own economic agenda, to fill the vacuum left by the failure of the Conservative vision. The modest infrastructure spending and small, temporary deficits that form the centrepiece of the Liberal macro plan certainly do not constitute an alternative agenda. So we have a lot of work to do.

In conclusion, I believe that the power of progressive economic ideas has become modestly stronger in Canada. The federal election campaign both reflected progress that was already underway (on issues like inequality and climate change), and incrementally contributed to that progress (through the way that some key issues, like deficits and pensions, were addressed by the competing parties and received by Canadians). Of course, the new Liberal government has a modest agenda, it will be receptive to business demands, it will compromise and abandon key promises, and its vague commitment to “change” will soon be tarnished. Alex Himelfarb, speaking to the Ontario CCPA’s excellent post-election roundtable, summed it up perfectly: This government will do less harm, and be open to more good, than the last one. But how much good it does, depends totally on how much it is pushed by us.

My judgment on whether the election advanced or undermined progressive economic ideas is not based on who won, so much as on how economic discourse among Canadians – so-called “common sense” – has evolved and is evolving. That is more important in the long run. The end of the election is just the beginning of our continuing work as advocates on all of those issues, as we continue to engage in the ongoing “battle of economic ideas.” But I am somewhat more optimistic about the prospects of that work than I was a year ago.